Sentence Structure

This section has discussed some basic elements of grammar, including major parts of speech and punctuation. Now it is time to put all those parts together to discuss what makes up a sentence. A sentence is a group of words that expresses a complete thought. A sentence must:

Examples: Sentences explain full thoughts, ideas, and actions to a reader. Can you envision an essay full of incomplete sentences? It would be confusing to understand. Complete sentences are necessary in academic writing. Further, can you imagine what a paragraph with only one kind of sentence might sound like? It would be boring for the reader. It is helpful to vary sentence structure throughout an essay to hold readers’ attention. There are only three major types of sentence structures: simple sentences, compound sentences, and complex sentences. All three are important to use in academic writing. Simple SentencesSentences with one independent clause and no dependent clauses are simple sentences. An independent clause is a group of words that contain a subject and verb and expresses a complete thought. A dependent clause is a group of words that contain a subject and a verb but does not express a complete thought.

Examples: A sentence with multiple independent clauses but no dependent clauses is a compound sentence. Multiple independent clauses need to be connected by a semi-colon (;) or a comma (,) and conjunction. Conjunctions are words such as and, but, for, nor, yet, or, and so.

Examples: A sentence with one independent clause and at least one dependent clause is a complex sentence. Independent clauses and dependent clauses are sometimes (although not always) connected by a comma.

Examples: There are sentences called compound-complex sentences, which combine a compound sentence with a complex sentence. These sentences contain two or more independent causes and one or more dependent clauses.

Examples: Sentence FragmentsIf you have a cookie, would you rather eat half the cookie or the whole cookie? It is a fair guess that you would rather have the whole cookie. The same applies to sentences. Why have part of a sentence when you can have a whole sentence? A fragment is like having a half of a cookie. Typically, complete sentences are what you want to aim for in academic writing. The tricky part is that a fragment looks like a sentence because it starts with a capital letter and concludes with end punctuation like a period. The problem is that fragments lack a main clause. A main clause is composed of three things:

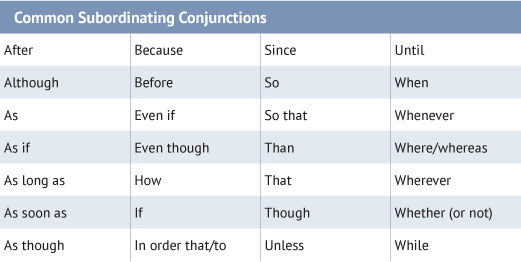

1. While Mary finished her homework. There may appear to be a subject (Mary) and a verb (finished); however, there is a subordinating conjunction at the beginning of the clause (while). A subordinating conjunction is a joiner word that introduces a dependent clause and joins it to a main clause. When a subordinating conjunction is added to the beginning of a clause, what appears to be the subject and verb can no longer function as the subject and verb. The clause must be added to the beginning or end of an independent clause to make it a complete sentence. The reverse can be true too. Take an independent clause and transform it into a fragment by adding a subordinating conjunction. For example, “Mary finished her homework” is a complete sentence. Add the word “while” to the beginning of the sentence to create a dependent clause.

2. The athlete sitting on the field waiting for practice to start. There is a subject (athlete), but there is no main verb or complete thought. 3. And talked loudly enough to cause the class to stare. There is a main verb (talked); however, the sentence is missing a subject and a complete thought. If we know fragments ought to be avoided, then we need to know how to fix them. Fragments can be fixed by ensuring there is a complete thought and either connecting the fragment to a main clause or revising the fragment to add a main clause. Now, look at the examples above again.

This seems easy enough, right? Fragments are not hard to fix. What is challenging is identifying that a fragment exists.

Run-On Sentences and Comma SplicesHave you ever been on a long car ride and the person next to you will not stop talking? You try to shut out the noise, but the talking will not end? This is what a run-on sentence sounds like to a reader. A run-on sentence is a sentence that is missing necessary punctuation, causing confusion and frustration for your reader. It is a misconception, however, that all run-on sentences are long sentences. Many run-on sentences are lengthy, but a run-on sentence can be short or long. What matters is that a run-on sentence is missing key punctuation, regardless of length. A comma splice is similar to a run-on sentence. It is a sentence where the wrong punctuation mark—in this case, a comma—cuts up or splices the sentence. Run-on sentences and comma splices are both compound sentences that are not punctuated correctly. A compound sentence is a sentence with multiple independent clauses but no dependent clause. Here are five options to fix run-on sentences and comma splices:

Multiple independent clauses can be fixed by separating the clauses into two separate sentences. They can also be connected by a semicolon (;) or a comma (,) and coordinating conjunction such as so, but, and, or, yet, for, or nor. Another option is to add a semicolon followed by a conjunctive adverb followed by a comma. Conjunctive adverbs are words such as however, therefore, hence, nevertheless, or thus. Finally, to fix a run-on sentence or comma splice, add a subordinating conjunction to make one of the clauses dependent. Subordinating conjunctions include words such as because, although, while, if, or after. This may seem difficult to understand at first, but these examples of run-on sentences may help: Run-On Sentences1. Incorrect: They were not just students they were proud Lopes! 1. Correct: They were not just students; they were proud Lopes! 2. Incorrect: I did not know I needed to apply for an internship early in college I was overwhelmed when my professor mentioned it to me. 2. Correct: I did not know I needed to apply for an internship early in college, so I was overwhelmed when my professor mentioned it to me. 3. Incorrect: She could not wait any longer to hear whether she received the scholarship it was her time to shine. 3. Correct: She could not wait any longer to hear whether she received the scholarship. It was her time to shine. 4. Incorrect: She thought about going to a state university she realized that GCU was a better fit for her. 4. Correct: She thought about going to a state university; however, she realized that GCU was a better fit for her. 5. Incorrect: Arnoldo persevered in his study of calculus he ended up doing well in the class. 5. Correct: Because Arnoldo persevered in his study of calculus, he ended up doing well in the class. Comma Splices1. Incorrect: They were not just students, they were proud Lopes! 1. Correct: They were not just students; they were proud Lopes! 2. Incorrect: I did not know I needed to apply for an internship early in college, I was overwhelmed when my professor mentioned it to me. 2. Correct: I did not know I needed to apply for an internship early in college, so I was overwhelmed when my professor mentioned it to me. 3. Incorrect: She could not wait any longer to hear whether she received the scholarship, it was her time to shine. 3. Correct: She could not wait any longer to hear whether she received the scholarship. It was her time to shine. 4. Incorrect: She thought about going to a state university, however she realized that GCU was a better fit for her. 4. Correct: She thought about going to a state university; however; she realized that GCU was a better fit for her. 5. Incorrect: Arnoldo persevered in his study of calculus, he ended up doing well in the class. 5. Correct: Because Arnoldo persevered in his study of calculus, he ended up doing well in the class. To prevent sentences from carrying on too long or becoming choppy with unnecessary commas, avoid run-on sentences and comma splices. Doing so is one way to ensure smooth, clear writing. Pronoun Agreement and Pronoun ReferenceA pronoun is a special or different version of a noun. A pronoun is a general way of referring to a specific person, place, or thing. Here are the most commonly used pronouns in the English language: anyone, anything, everyone, everything, he, her, him, himself, I, it, itself, me, myself, nothing, one, she, someone, something, them, themselves, they, us, we, who, you.

Some pronouns are definite in that they replace a specific person, place, or thing or another pronoun. However, sometimes things are not so clear. What do we do in these situations? We use what are called indefinite pronouns. Indefinite pronouns refer to a non-specific noun, which include words such as all, any, anyone, anything, each, everybody, everyone, everything, few, many, nobody, none, one, several, some, somebody, and someone. Indefinite pronouns seem simple, so what is the catch? The catch is determining whether the indefinite pronoun is singular or plural. Here is a chart to help you:  Pronoun Agreement

Pronoun Agreement

When using a pronoun, you have to ensure that the pronoun agrees with the word it replaces, which is called its antecedent. The rules are simple. A singular antecedent requires a singular pronoun; a plural antecedent needs a plural pronoun. For example, “The girl searched her purse for her cell phone” makes sense. It does not make sense to say, “The girl searched their purse for their cell phone.” If you have multiple singular nouns, then together they become a plural antecedent. For example, in the sentence, “The five students need their laptops” is correct rather than “The five students need her laptop.” The exceptions to this rule are the words each and every. They are usually singular and require a singular antecedent. For example, “Every friend of mine is a friend of yours.” It would be incorrect to say, “Every friend of mine are a friend of yours.” Are is a plural verb, but each and every are singular pronouns. A gendered antecedent should match its gendered pronoun. Typically, Megan is a female’s name, so it is generally accurate to say, “Megan sped her car off into the sunset when she saw the flashing lights in her rearview mirror.” It would not make sense to say, “Megan sped her car off into the sunset when he saw the flashing lights in her rearview mirror.” Pronoun ReferenceHave you ever heard someone say, “Well, they said it was true!” You probably cannot help but shout, “Who is this 'they' you are talking about anyway?” If you are not specific enough, pronouns can be confusing for readers. Words like it, they, this, that, these, those, and which should be used carefully to prevent confusion. Pronouns should clearly refer to an antecedent. Here are some examples:Incorrect: The daughter asked the mom to put gas in her car. This sentence is confusing because it is unclear whose car it is. Is it the mom’s car or the daughter’s car? Revised: When the daughter could not figure out how to put gas in her car, she asked her mom to help. Incorrect: Sara and Julie are best friends, but she is the sweet one. This sentence is ambiguous. Who is the sweet one? Sara or Julie? The sweet one is unclear in this sentence. Revised: Sara and Julie are best friends; Julie is the sweet one. Incorrect: He enjoys working out, playing the guitar, and hanging out with friends, but that is his favorite. What does that refer to in the sentence above? It is unclear. Revised: He enjoys working out, playing the guitar, and hanging out with friends, but hanging out with friends is his favorite. Modifiers

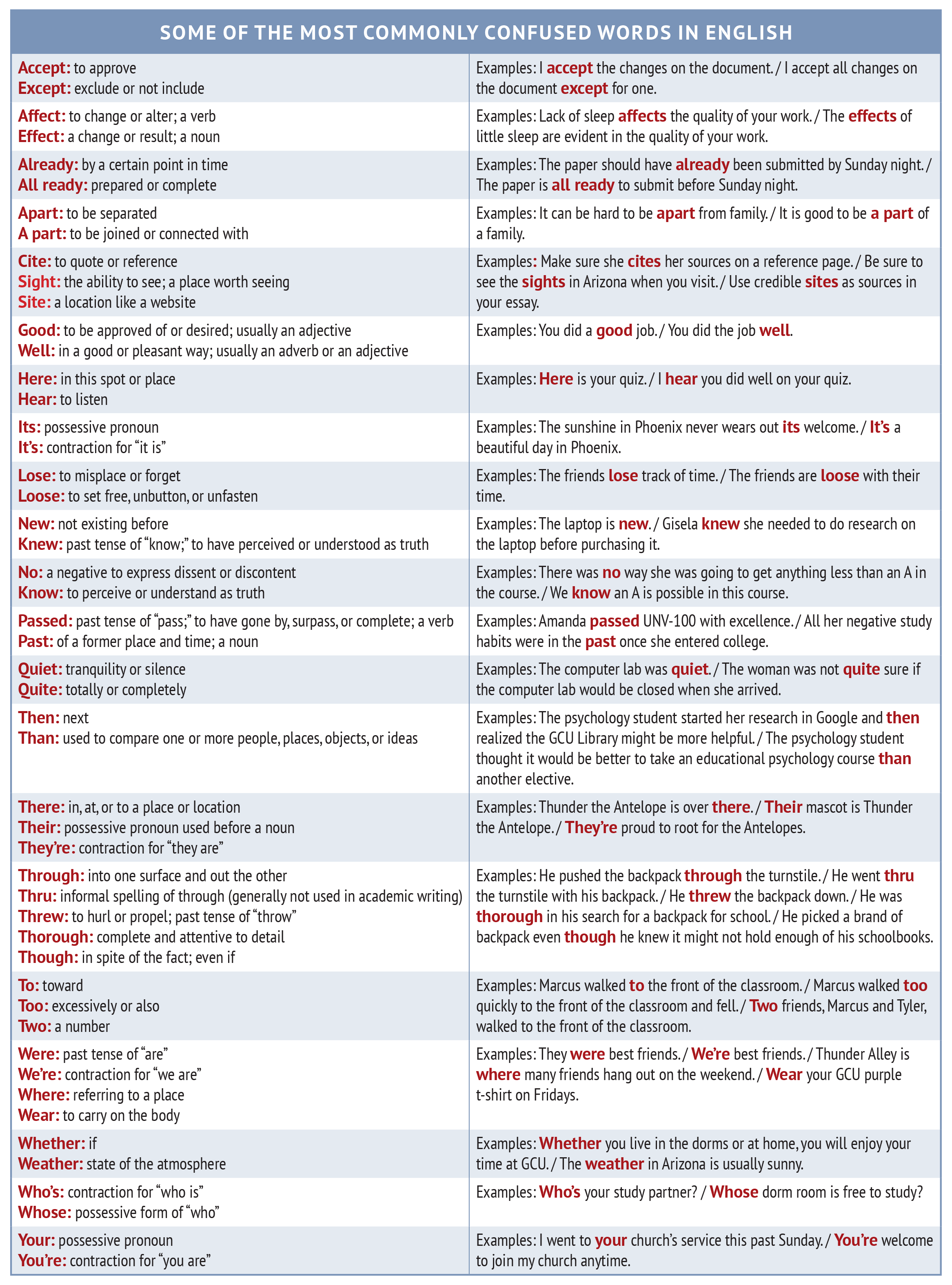

Everyone has one friend who adds spice to life. This friend knows how to make people laugh and feel comfortable. This is exactly what a modifier does for other words in a sentence. A modifier is a word or phrase that adds details or support to other words in a sentence. Here are some examples of modifiers in sentences: He is the guy with the flat-billed hat. The tough part about friends who are the life of the party is that they sometimes become friends with people they should not, causing them to end up in the wrong place at the wrong time. When descriptive words are in the wrong location or do not appear to modify anything, this is called a misplaced or dangling modifier. Misplaced ModifiersIn a sentence, when the subject of the modifier is unclear because the modifier is placed poorly, it is called a misplaced modifier. The modifier is literally out of place. Modifiers should be placed next to the word or words they describe. Misplaced modifiers confuse readers making it difficult to tell which subject the word is modifying. To fix the errors below, the modifiers are moved next to its target in the sentence. Incorrect: She saw a saguaro cactus on the drive to Arizona. Correct: On the drive to Arizona, she saw a saguaro cactus. Incorrect: The friends walked towards their car carrying overnight bags. Correct: The friends carrying overnight bags walked towards their car. Incorrect: We returned the car to the car lot that stalled on the highway. Correct: We returned the car that stalled on the highway to the car lot. Dangling ModifiersLike misplaced modifiers, dangling modifiers cause readers confusion too. These sentence errors create inelegant and choppy sentences. Dangling modifiers are words that are intended to describe others, but they are placed poorly and, therefore, do not modify anything. Dangling modifiers are often found at the beginning of sentences, although occasionally they are found at the end of sentences too. To fix a dangling modifier, add a target for the modifier and then revise the remaining words. Incorrect: To please her friends, the music in the car changed. Correct: To please her friends, Alison changed the music in the car. Incorrect: Upon entering the classroom, the big screen at the front of the room caught my attention. Correct: Upon entering the classroom, I noticed the big screen at the front of the room. Incorrect: Deciding to matriculate into GCU, her mother enthusiastically hugged Rafi. Correct: When Rafi decided to matriculate into GCU, her mother enthusiastically hugged her. Commonly Confused WordsAre we going there, their, or they’re? Are you feeling good or well? Did I hear or here you correctly? Is the weather or the whether nice? Do you know which commonly confused word is the best fit in each sentence? Did some of these sentences confuse you? If so, that is okay. This is because there are many words in English that look or sound alike but have different meanings. There are also times when the American spelling of a word and the British spelling of a word are different causing added confusion. This section highlights some of the most commonly confused words, their meaning, and examples. The answers to the questions above are: We are going there. She is feeling well. I hear you correctly. The weather is nice.

The list in this section defines some of the most commonly confused words in English. Of course, there are more commonly confused words found in writing and every day conversation. Can you think of some others? Academic Writing ConventionsImagine driving a car down a busy road. Now imagine driving on that busy road without any laws or regulations. Cars would swerve everywhere and traffic would be unbearable. The drive would feel unsafe, possibly even dangerous, since everyone would be following his or her own rules. This is similar to academic writing. Laws and regulations on the road can be applied to the conventions of academic writing. Conventions are expectations or customs that writers follow. Every kind of writing has its own rules. For instance, you probably would not write an email to your boss the same way you would text a friend.

Conventions keep academic writing orderly and logical. When a writer follows the conventions, at least to a degree, the reader has a better chance of understanding the purpose of the text. Thanks to conventions, even with little knowledge of college-level writing, a reader can pick up an essay and understand its intent. To drive a car safely down a road, we need to know the uses and expectations of the road. This is true for conventions of academic writing. College students are expected to follow certain conventions in their writing, and you should learn these rules so you can be successful. It may seem like the rules are random, but they are helpful guidelines to show you are part of an academic community. Although every instructor has individual preferences and the rules are not absolute, there are general expectations or customs in academic writing you can expect. This section highlights key features of academic writing conventions, including tone, slang, clichés, point of view, and contractions. Tone Tone has many meanings; however, in writing, tone refers to a writer’s style, character, bias, or attitude. The right tone can separate a writer who is taken seriously from one who is not. A writer’s tone will differ with each assignment. In general, tone in academic writing is more formal than tone in personal writing. Casual written or spoken expressions typically are not used in formal academic writing. For example, a casual message like “Can’t wait to see ya later!” might be okay when writing to a friend, but it would be too informal for academic writing. You may use playful or inside jokes when communicating with a friend, but this would not be appropriate in a formal work proposal. You may be wondering if academic essays have to be dry or full of jargon. The answer is no. Academic writing can be simple, clear, and engaging. A dull and boring essay rarely earns an A. Understand your audience and what you are trying to achieve with your writing. Read the assignment guidelines, make sense of the essay’s purpose and audience, and reach out to your instructor. These techniques will help you achieve the appropriate tone for an academic essay. SlangAvoid slang to achieve a formal tone in academic writing. Slang is an informal form of language often used in speech, but it does not usually have a place in academic writing. Words like klutz, grub, cushy, and cool are examples of slang. What are some examples of slang you have used this week over text, email, or in a conversation with a friend? Clearly, slang words are not terrible. They may be appropriate in informal conversations, but slang is not appropriate for most academic writing. Try reading your writing aloud to avoid slang. You can try reading your writing aloud to a friend too. If there are words that sound conversational, replace them with more formal words. Clichés “That is so cliché?” Have you heard this expression before? A cliché is a phrase, expression, or idea that has been overused so much that it has lost its originality and impact. We use them in speech every day—sometimes without realizing it. Common clichés include, “a waste of time,” “time heals all wounds,” “opposites attract,” “find your way,” “keep the faith,” and “all over the map.” Take a minute to jot down five common clichés used in conversations with friends and family. Like slang, clichés are not bad. They are better in conversation though than academic writing. Clichés can be tough to identify. We use them often, so they may not seem like clichés at first. If you read your writing and see a phrase that is unoriginal, revise it into your own words. Your unique words are far more powerful than a phrase overused by many every day. Point of View in Academic WritingYour professor may tell you to avoid using “first and second person” and to use “third person.” Who are these so-called "persons"? First person point of view refers to the use of first-person pronouns I, me, we, and us in writing. Usually, professors ask students to avoid first person in academic writing. First person can appear too casual or biased to an academic reader. The exception to this is when you are asked to write a paper about your personal experiences, then the use of first person is acceptable. When in doubt, assume first person should be avoided, and ask your instructor for clarification. Example: “I believe the U.S. government needs to regulate businesses.” Corrected: “The U.S. government needs to regulate businesses.” Second person point of view refers to the use of the second-person pronoun or you in writing. Generally, second person is avoided in academic writing. It can sound informal and even accusatory to a reader. Example: “If you learn how to write well, you will do better in school and earn better grades.” Corrected: “Learning to write well in college helps students do better in school and earn better grades.” Third person point of view refers to the use of third person pronouns like he, she, they, and it. Third person is useful in all types of writing, including academic writing. Example: “Grand Canyon University students succeed if they prepare thoroughly for quizzes and exams.” Most academic essays should be written in the third person, second person should be avoided, and the first person should only be used if approved by a professor or when writing about a personal experience. Finding references to point of view in your essay can be a fun task. Make your search for point of view in your writing into a scavenger hunt. Track down second person point of view references and eliminate them. Look for first person pronouns and remove them unless approved by your instructor. If you see references to third person, give yourself a mental high five. Job well done! ContractionsWhen you combine two words by leaving out a letter or two and replacing the letters with an apostrophe, it is called a contraction. Contractions are casual and, therefore, not often used in academic writing. Here are some popular contractions:

Conclusion

It is not easy to master the English language. The authors of this text learn more about the English language every day. Hopefully, this chapter has taught you that grammar matters. Using appropriate grammar, punctuation, spelling, and writing conventions, as well as understanding when to follow certain rules, can help you gain access to various opportunities such as jobs and scholarships. Appropriate grammar can even lead to improved grades. You may want to review the text in this section a few times until the concepts are clear. Keep making the effort, and grammar will get easier in time. Would you like to test the knowledge you have learned? Return to the beginning of this chapter and take the self-test again. See how many questions you get right this time. Regardless of how well you do on the self-test, keep traveling down the road to a better understanding of grammar, punctuation, and conventions. The long and winding journey will be worth it in the end. |