IntroductionDoes the word grammar strike fear into your heart? Do the endless rules of the English language send you into a fit? If so, you are not alone. Many college students find grammar, punctuation, and conventions to be challenging. Although good grammar in speech and writing are important, it admittedly does not make the rules easier to learn. There are many expectations to follow, and sometimes these rules vary by context. This section of the text will guide you through the essential parts of speech and common usage rules needed to succeed in college-level writing. The exercises will help you to understand the terms and put them to use in your own writing. Grammar, punctuation, and conventions vary depending on context. For instance, on occasion, commas are used differently in academic writing than they are in marketing or business writing. In this section, we will focus on general usage rules found in many types of writing with a special emphasis on academic writing. The section begins with an overview of why grammar and punctuation matter and then journeys to smaller parts of sentences, specifically parts of speech, to sentences, moving on to sentence-level errors, commonly confused words in academic writing, and ending with a discussion about academic writing conventions. Grammar and Punctuation UsageWhat Are Grammar and Punctuation?The words grammar and punctuation are discussed in school and in conversation, but what do these words mean and what purpose do they serve? Knowledge of basic grammar and punctuation rules is necessary to be a successful academic writer. What would an essay look or sound like if the ideas in the essay were creative, but there were countless misspellings or missing punctuation? Grammar is the whole system and structure of the English language. It includes the rules and expectations of what we say and how we say it. The rules and expectations can be tricky to remember, but they offer a set of guidelines to help us communicate more clearly. Punctuation is the marks used in writing to separate parts or all of a sentence. It is much easier to understand what a sentence or part of a sentence means because of punctuation. Punctuation includes marks like commas, periods, colons, and semicolons. Imagine a paragraph without a single period or comma. You may understand the words in the paragraph, but it would be difficult to decipher its meaning without punctuation. Why Grammar and Punctuation MatterThe purpose of grammar is to ensure that what you write and what you say is easy to understand. In short, good grammar can lead to good communication. Opportunities like jobs, scholarships, and internships are possible when you communicate clearly. A simple change in a sentence can alter its meaning. For example, the sentence, “The student’s grades were improving,” suggests that one student’s grades are on the upswing. However, the sentence, “The students’ grades were improving,” says that many students are getting better grades. Simply moving the apostrophe a single place changes the sentence’s meaning. All of this may make you wonder: "If there are so many rules, how will I ever learn them?" Being an expert on grammar is not necessary. Knowing where to turn to fix the issues is what matters. There are resources available to help you learn the rules, like this section of the text. You can refer to these resources any time you have a question about grammar or punctuation. Key TermsThis section covers essential terms like nouns, pronouns, subjects, verbs, comma splices, fragments, apostrophes, clichés, tone, contractions, modifiers, and prepositions. This list may seem long; however, help is on the way. No longer do you need to feel like a driver stranded on the side of the road, desperately waiting for help. You will learn each term one at a time and then put everything to use by testing your knowledge of the rules. Subjects and VerbsMany of you remember learning the terms nouns, subjects, and verbs in Language Arts class in elementary school. You may recall definitions such as nouns are words that represent a person, place, thing, or idea, and that a subject is a noun that is doing or being something, while a verb is any action word. The words or definitions may still be present in your mind, but there are more to these terms than may appear at first glance. A subject, verb, and complete thought are all you need to make a sentence. These three parts are a sentence’s building blocks. Just as a car needs a motor, tires, and gasoline to function, without a subject, verb, and complete thought, you have no sentence. Identifying subjects and verbs will enhance your ability to write complete sentences.

Subjects A subject is a person, place, thing, or idea that is doing or being something in a sentence. To identify a subject in a sentence, it helps to find the verb or action word first. If you identify the verb, ask yourself who or what is affecting the verb. This is your subject. For example, “The president closed the college for the day because of extreme heat.” In this sentence, the subject is president since he or she is the person closing the college. This seems simple enough, right? Like most things in life, there is more to subjects than that. There are four primary kinds of subjects:

Subjects and verbs are related. What would a subject be if it did not do anything? The subject would be boring, stagnant, and stale, so a verb gives life to the subject. A verb is a word that represents an action or a state of being. Verbs are doing words. These words denote one or more of the following:

Like subjects, there are several kinds of verbs, including action verbs, linking or state of being verbs, helping verbs, and compound verbs. If you identify a verb, then you can identify the subject. For example, “Sheila runs every day after work.” The action word is runs and, therefore, the verb in the sentence. Sheila is the person being affected by or affecting the verb and, therefore, she is the subject in the sentence. Action VerbsDance, scream, jump, and shout are action words. These words express something that a person, place, thing, or idea can actually do. ExamplesMax coached Charlie on how to throw a football. Jamal built a temporary cover to protect himself from the rain. Linking VerbsLinking or state of being verbs: Linking or state of being verbs connect the subject of the sentence with information about it. They do not show any action. Instead, they connect to a verb that represents a state of being. There are eight linking verbs: is, am, are, was, were, be, being, and been. ExamplesThe young girl is tall for her age. Laura was thrilled to pick up her new beach cruiser. Helping VerbsEverybody needs help from time to time. This is exactly what helping verbs do for main verbs. On their own, helping verbs do not communicate much, but they support the main verb and offer meaning. Helping verbs include am, is, was, were, been, seem, appear, being, and be, as well as the verbs have and do.

Infinitives are “to + a verb” words. Some verbs require helping verbs to show tense. -ing words and “to + a verb” words require helping verbs every time they function as verbs. For example, in the sentence “The lifeguards are draining GCU’s swimming pool,” are is the helping verb and draining is the gerund. In the sentence, “Her biggest goal is to play basketball for GCU,” is is the helping verb and to play basketball is the infinitive phrase.

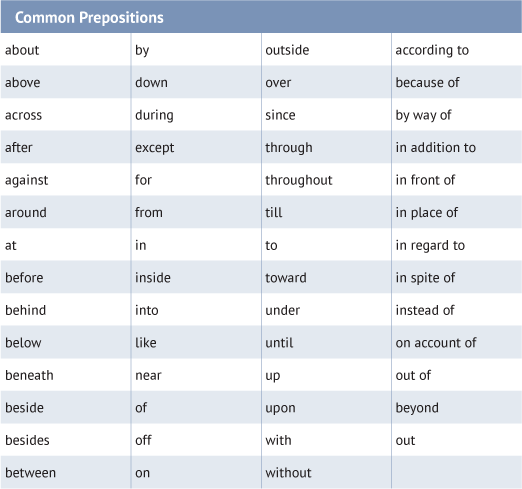

Katrina was playing soccer. I have finished my essay for Sunday night. Compound VerbsThere are two kinds of compound verbs: more than one verb in a sentence and a single verb made up of more than one word. ExamplesSomeone will need to edit my essay. We can sound proof our dorm Prepositions and Prepositional PhrasesOn a road trip, everyone needs a buddy to tag along who connects all the friends together and gets everyone moving in the same direction. This friend is like a preposition or prepositional phrase. Prepositions add interest to a sentence and describe a noun’s relationship with other words. Usually, prepositions and prepositional phrases suggest a period of time or a location. Thunder the Antelope is on the basketball court. The words on, in, and around in these three sentences tell the reader more about where Thunder is located in the arena.

There are more than 150 prepositions in the English language. Here is a chart listing common prepositions:

Prepositional phrases, are an expanded form of a preposition; they are a series of words that start with a preposition and end with a noun or pronoun. Prepositional phrases function as adverbs or adjectives. All of this may sound complicated, but it is not too complex. These phrases give extra information about the noun. Here are a few examples: She made her way from campus. There are two main kinds of prepositions: prepositions of time and prepositions of place. Prepositions of time give information about a specific period of time, date, or part of the day. For example, in the sentence, “We will visit you on Wednesday.” On Wednesday is the prepositional phrase, suggesting the day of the week they will visit. Prepositions of place give additional information about someone or something’s location. For example, in the sentence, “The dog is under the table.” Under the table is a prepositional phrase that explains where the dog is located. Confusing Nouns in Prepositional Phrases as SubjectsSome of you may be wondering, “What’s the difference between subjects and verbs and prepositional phrases since they seem so similar?” Here is why they are different: The subject will never be part of a preposition phrase. Prepositional phrases are simply there to add extra information about place and time. They are not there to replace the subject of a sentence.

Subject/Verb AgreementIf the family car breaks down and you and your family are stranded on the side of a road, would you call someone with a one-seater motorcycle to come pick up everyone? No, it would be more useful to call someone who can pick up the entire family and take them to a safe location. The same applies to subjects and verbs. Singular denotes one. Plural denotes more than one. A plural subject needs a plural verb, and a singular subject needs a singular verb. If you try to put a plural subject with a singular verb or vice versa, they do not match. Subject/verb agreement errors can cause confusion for readers because they cannot identify who is doing what and how many are doing what. In the sentence, “The vocalists sings,” the plural subject vocalists does not match the singular verb sings. It should be, “The vocalists sing.” Here is another example, “The student are doing so well they can pass the course with an A.” The singular subject student does not match with the plural verb are doing. The sentence should read, “The students are doing so well they can pass the course with an A.” There are such things as collective nouns. These are a special class of singular nouns because the group forms one collective unit, such as the words audience, department, family, society, team, and committee. Naturally, there are exceptions to this. Even though collective nouns usually are singular, there are times when the group is all doing their own thing. For example, in the sentence "Dr. Arcos’s class started its first major 200-point test," all members of the class are taking the same test at the same time, so class is singular and takes a singular verb its. But in the sentence, "Dr. Arcos’s class started their research papers on how fun English can be," the students are starting their research papers at different times, in different places, on different subjects, so class is a plural noun and their is a plural verb. Proper subject/verb agreement can have a positive impact on your reader. It shows your reader that you are detail oriented and aware of what you are trying to describe. TenseTime is of the essence, or so the saying goes. What does time have to do with writing? Plenty! In English, verbs have a sense of time. Verbs are doing words. There are three main times used in English to convey information: past, present, and future. By giving verbs a sense of time, an audience can determine whether something is happening now, has already happened, or will happen in the future. For instance:

It is easy to keep tense consistent in conversation. Many of us do it subconsciously. It is much harder in writing though. We have to make an effort to keep tense consistent. When a change occurs in verb tense in a sentence or a paragraph, it is called a tense shift. For instance, if a paragraph is written in present tense and suddenly jumps to past tense, it can be jarring for a reader. Here is an example: “This study addresses research on effective study habits for college students. The authors show that studying in increments every day improves test scores. They also showed that taking notes leads to high scores on exams.” Notice how the paragraph is written in present tense until the word “showed,” which is past tense. The switch in tenses is noticeable and can cause confusion for the reader. There are occasions when it is necessary to shift tense. For instance, when we describe things that happen (or might happen) at different times, it is appropriate to shift tense. In the following sentence, “We will go to the gym before we eat breakfast but after we have had our coffee,” it is logical to use different tenses to reflect actions that took place at different times. CommasDriving the open roads of the desert may seem long and boring, but fortunately there are road signs to let you know the miles until your next destination. The green signs along the side of the road give you hope that you will eventually reach your destination. Road signs are like commas in a sentence. Commas are a form of punctuation that break up long sentences into smaller chunks. Misplaced or missing commas are confusing for readers, making writing difficult to comprehend. Comma errors also indicate carelessness on the part of the writer. Check out these myths on commas:

Although commas may seem confusing, they can be easy if you learn five major uses for commas:

This rule is straightforward: Use commas to separate three or more words, phrases, or clauses in a series. Do not put a comma before the first item on the list. In the sentences below, there are three items in the series: good vision, a steady grip, and gasoline for the car. Incorrect: Driving requires, good vision, a steady grip and gasoline for the car. Incorrect: Driving requires good vision, a steady grip and gasoline for the car. Correct: Driving requires good vision, a steady grip, and gasoline for the car. Commas with Introductory Words and PhrasesIntroductory words like however, still, furthermore, and meanwhile create flow from one sentence to the next. If an introductory word starts a sentence, it needs a comma after it. For instance, “Furthermore, the researcher proved her argument through ample evidence,” or “However, the facts of the case still need to be clarified.” Introductory phrases set the stage for the reader, prepping him or her for the main action of the sentence. These phrases cannot stand alone as a sentence. Instead, introductory phrases prepare the reader for the action to come in the sentence. Place a comma after an introductory phrase in a sentence, such as an introductory prepositional phrase. For example: Incorrect: After correcting the essay’s issues she submitted her work to LoudCloud. Correct: After correcting the essay’s issues, she submitted her work to LoudCloud. Incorrect: To stay in shape the women did Pilates and yoga. Correct: To stay in shape, the women did Pilates and yoga. Incorrect: A respected leader the university’s president is intent on taking Grand Canyon to new heights. Correct: A respected leader, the university’s president is intent on taking Grand Canyon to new heights. Commas with Dependent and Independent ClausesA dependent clause is a group of words that contain a subject and a verb but does not express a complete thought. It is dependent because it cannot stand alone and depends on the rest of the sentence for context and meaning. Place a comma after a dependent clause when it is located at the beginning of a sentence. For example: Incorrect: When Jaime started studying for her exam she knew it was going to be tough to earn an A. Correct: When Jaime started studying for her exam, she knew it was going to be tough to earn an A. Incorrect: Because her best friend lost her textbook Mary will struggle to pass her exam. Correct: Because her best friend lost her textbook, Mary will struggle to pass her exam. When a dependent clause comes after the independent clause, you generally do not use a comma. For example: Incorrect: Jamie knew it was going to be tough to earn an ‘A,’ when she started studying for her exam. Correct: Jaime knew it was going to be tough to earn an ‘A’ when she started studying for her exam. Incorrect: Mary will struggle to pass her exam, because her best friend lost her textbook. Correct: Mary will struggle to pass her exam because her best friend lost her textbook. Common dependent markers that start dependent clauses are, after, although, as, because, even, since, though, unless, until, when, whether, and while. An independent clause is like a dependent clause except for one major difference: It is a complete sentence and expresses a complete thought. It is independent, so it can stand on its own. The following are two examples of independent clauses, “My friends refuse to ride in his junky car” and “We are going to take our other friend’s car instead.” If you wanted to combine these two clauses, a comma alone is not a strong enough form of punctuation to connect them together. To fix the issue, use a semicolon (;) instead of a comma (,) to connect the independent clauses. For instance: Incorrect: My friends refuse to ride in his junky car, we are going to take our other friend’s car instead. Correct: My friends refuse to ride in his junky car; we are going to take our other friend’s car instead. You can also add a conjunction and a comma to punctuate two independent clauses. Conjunctions connect independent clauses and include words such as and, but, for, nor, yet, or, so. For instance, “My friends refuse to ride in his junky car, so we are going to take our other friend’s car instead.” Commas in the correct place can ensure your writing flows and makes sense to your readers. Keep this in mind as you include dependent and independent clauses in your writing. Commas with Sentence InterruptionsTherefore… However… As a matter of fact… For instance… These words appear often in academic writing, but how are they punctuated? There are two ways to use commas to punctuate sentence interruptions like these. If the interruption starts a sentence, follow it with a comma. Examples: “Therefore, the problem was resolved,” or “For example, planes, trains, and automobiles are the most common ways to get around this great nation.” When words interrupt the middle of a sentence, they usually are enclosed in commas. For instance, “As the semester moves along, of course, students will reach out to the Instructional Assistant” or “Truly, readers, the book is well worth your time.” Can you think of any other words or phrases that might function as sentence interruptions? Commas with Direct QuotationsCommas always go inside direct quotations, whether or not they are a part of the quotation. Take a look at these examples: Incorrect: Mary explained, “There are many important reasons to learn comma rules”, so she proceeded to learn the rules by heart. Incorrect: “Listen to the curfew rules”, the mother explained. Notice that the quotation mark is placed incorrectly outside the direct quotation. Now, note that the quotation mark is placed inside the direct quotation. Correct: “The U.S. government needs a system of checks and balances,” Senator Smith claimed. Correct: She stated that Dr. D. was “the best professor she has ever had,” and she gave him perfect scores on the end of course survey. Certainly, there are a variety of uses for commas. There are lingering myths about commas too. Remarkably, more uses for commas exist than are discussed in this section, but if you follow the five primary uses, you will be well on your way to successful comma use. ApostrophesLike gasoline in a car on a long road trip, the apostrophe is a form of punctuation that has seemed to disappear over time. Apostrophes have gone missing in writing in everything from the media to marketing. Take the phrase “New Year’s Eve” for instance. Now, it is often written as “New Years Eve.” On road signs, we sometimes see “Dont Walk,” even though it should be, “Don’t Walk.” Although the apostrophe is forgotten at times, do not be fooled. Apostrophes serve an important purpose in writing. They show possession of a noun and show the omission of letters. Apostrophes are found commonly in academic writing. Understanding how and when to use them is important. Apostrophes to Show PossessionThe most noticeable way apostrophes are used in writing is to show possession. When someone or something belongs to another someone or something, we use apostrophes to show this; otherwise, a reader might not know there is possession involved. For example, if you write, “U.S. Route 20 is Americas longest road,” it is not clear that the United States owns or possesses the road. Instead, the sentence should read, “U.S. Route 20 is America’s longest road.” To show possession, there are different rules for singular noun and plural nouns. Singular means one. Plural means more than one. Apostrophes with Singular NounsAdd an apostrophe plus the letter “s” to show possession with a singular noun. Examples: student’s backpack, laptop’s mouse, Tyrone’s girlfriend, or Maritza’s classmate. If a noun is singular and possessive and ends with the letter “s,” GCU and APA Style suggests adding an apostrophe and an “s.” For example, “James’s friends are cool” or “Jesus’s disciples were called.” Apostrophes with Plural NounsIf a noun is plural and possessive, place the apostrophe after the “s.” Note where the apostrophe appears in each of the following examples: students’ responsibilities, soldiers’ gear, friends’ cars, or celebrities’ hairstyles. There is an exception to this rule. If the noun is already written as a plural, such as children, women, men, and people, then “s” with an apostrophe is not needed. If a noun is plural and possessive and ends with the letter “s,” place an apostrophe after the “s.” For example, “The Jones’ car went from zero to 60 in 8 seconds.” Do not be tempted to use an apostrophe or assume possession exists simply because a word ends in “s.” For instance, “There are two cat’s in the backyard.” There is no possession in this sentence (the cats are not owning anything), so the sentence should read, “There are two cats in the backyard.” It helps to take a logical approach to apostrophes. Ask yourself: What is this sentence trying to say? For instance, if a sign at your old high school said, “Teacher’s Lounge,” this would not make sense. “Teacher’s lounge” would mean that the lounge belonged to only one teacher at the school. While it might make that one teacher happy, it is not accurate. The lounge belongs to all teachers in the school and should read “Teachers’ Lounge.” Apostrophes with Possessive PronounsPronouns are words that replace nouns. Possessive pronouns do not need apostrophes. This is because they already show ownership, and do not need an extra apostrophe to show this. Possessive pronouns that fit this category include words such as its, yours, his, hers, ours, theirs, and whose. For example, there is no need to use an apostrophe after the pronoun its to show possession. “The road is known for its winding curves” is correct. “The road is known for its’ winding curves” is not correct because no apostrophe is needed. You would not say, “I borrowed his’ book.” It should be “I borrowed his book.”

Apostrophes are the form of punctuation used in contractions, or a word in which one or more letters have been omitted and an apostrophe put in its place. Although apostrophes are common in academic writing, contractions are not used in academic writing. Contractions are used, however, in casual writing and in conversation. The full version of a word is ideal in academic writing. For example, the contraction don’t includes an apostrophe and should be written out as do not. Who’s includes an apostrophe and should be written out in academic writing as who is. Won’t should be written as will not. Whose is a possessive pronoun that can cause some confusion because whose can be mixed up with the contraction who is. “Who’s laptop is this?” does not make sense. The word who’s is a contraction for who is, so unless who is fits into the sentence, say, whose. In this case, “Whose laptop is this?” is correct. Again, there are two main reasons to use an apostrophe: to show possession and to replace missing letters. Always go back to these two uses before adding an apostrophe to a word. |