Before you begin reading this chapter, please take this quiz to see what you already know about comparing and contrasting.

IntroductionOne of the ways people understand what something is or what something does is to think about how it is the same or different from other things. How comfortable is the chair you are sitting in? You might say it is very comfortable, or you might use a comparison to say it is more comfortable than sitting on the ground. Even complex ideas can be understood this same way. It is important to take some time to consider what it means to compare and contrast because this is a very common method of making sense of the world that can be used incorrectly. You can compare ideas in an imprecise way and come to conclusions that do not represent either idea correctly. Have you ever heard of the expression, “comparing apples to oranges”? This expression is used when a person has made the mistake of comparing two things that do not have enough in common. Perhaps two ideas seem to have enough in common, but they are so different in one respect that it is not actually helpful to compare them to each other. Apples are fruits, and oranges are fruits, but is it fair to say that the apple you are eating is not a good apple because it is not as juicy as an orange? No, because apples are not supposed to be juicy. That is a poor comparison. Perhaps you have heard someone say, “Let’s compare apples to apples.” What do you think that means? The next paragraph is a more complex example of two things that might seem similar, but are not similar enough to make a useful comparison: The Sonoran Desert surrounding Tucson, Arizona, is nothing like the city streets of Central Phoenix, even though for many months of the year, these two areas both have temperatures reaching 100 degrees Fahrenheit. It is not smart to go barefoot in the desert or on the city streets. Both places have sharp objects on the ground that can cut a person’s feet. In the desert, it might be rocks or cactus spines. In the city, it might be broken glass. Some of the Sonoran Desert is located in Arizona and some of the desert spreads into Mexico. All of Phoenix, on the other hand, is located in Arizona. These two places have a few things in common, but are mostly different. Compare that paragraph to another one that compares the Sonoran Desert surrounding Tucson, Arizona, to the Mojave Desert that covers an area of Arizona farther north. The Sonoran Desert surrounding Tucson, Arizona, is nothing like the Mojave Desert, even though for several months of the year, these two areas both have temperatures reaching 100 degrees Fahrenheit. It is not smart to walk barefoot in either desert because the ground is rocky and there are cactus spines. On the other hand, the Sonoran Desert is much more beautiful than the Mojave Desert. The Mojave has dry lakebeds, scraggly scrub bushes, and the famously bleak Death Valley. The Sonoran Desert is lush in comparison. The Sonoran Desert grows the very impressive saguaros, bright green palo verdes, and tall ocotillos. In the spring, all these plants produce either bright and waxy, or airy and fragrant, bouquets of flowers bursting with pollen. These two places have a few things in common, but are mostly different. It is not quite as meaningful to compare the Sonoran Desert to Central Phoenix as it is to compare the Sonoran Desert to the Mojave Desert. The reader does not come to know either the desert or the city much better through comparison but can come to know the two deserts better through comparison. Part of the problem with the desert to city comparison is that the categories used to think about cities (population, housing, infrastructure, economy, and so forth) are not the same categories used when thinking about deserts. Another problem with comparing the desert to a city is that the purpose of the comparison is not clear. The reader can imply that the purpose for comparing deserts is to know each desert a little better. The implication for the purpose of comparing a desert region to a city center is pretty hard to guess. Purposes for Comparison and ContrastMaybe it seems obvious, but comparing is explaining how things are alike. Contrasting is showing how they are different. Many times we will use the term comparison to mean both how something is like and not like something else. It is helpful to think about the ways comparison and contrast are used into three purposes: to understand, to explore, and to persuade. Comparison and Contrast to UnderstandPeople compare things and ideas in order to understand them better. This is what you do when a friend asks, “What is that like?” "What does a rattlesnake taste like?" "What is it like to live in Phoenix?" Likewise, you can make sense of very complicated issues through comparison. For example, if you want to understand how people are coping with immigration along the U.S. border with Mexico, you might compare your current situation to other times in the county’s history, or you can compare people along the border to people who live along similar borders between other countries. Another word for this kind of comparison is analogy. An analogy is a kind of argument that explains what one thing is by comparing it to another. More specifically, an analogy compares one well-known thing to the thing we are trying to understand better. Metaphors and similes are also used to help you understand something better by comparing it to something familiar. MetaphorsComparison and contrast essays can sometimes be creative and even poetic when you use metaphors to help make your point. A metaphorical comparison adds imagery, passion, and emphasis. It takes your reader beyond the literal meaning of your words and says more than you can with words alone to evoke a stronger connection in your reader. For example, young desert tortoises are the quiet moving stones of the desert. Not literally, but metaphorically speaking. Get the picture? SimilesA simile is a useful figure of speech that is just slightly less poetic and slightly more formal than a metaphor. Similes use the words like or as. If you write that young desert tortoises are camouflaged because they look like stones, your reader still gets the picture, but your tone is different. For some topics, that is a good strategy. A simile is a kind of metaphor. What is the difference in tone between these two sentences? Rattlesnake tastes like chicken. Rattlesnake is the desert chicken. AnalogiesSometimes an analogy is described as an extended metaphor. In other words, an analogy is a metaphor that goes on for more than a few sentences. Another way to think of an analogy is that it is a long and thoughtfully constructed metaphor created to argue a specific point of view. An entire essay can be an analogy, or a writer might sustain an analogy for just one paragraph. Can you see how the following example of comparison and contrast using an analogy might be the start of an entire essay?

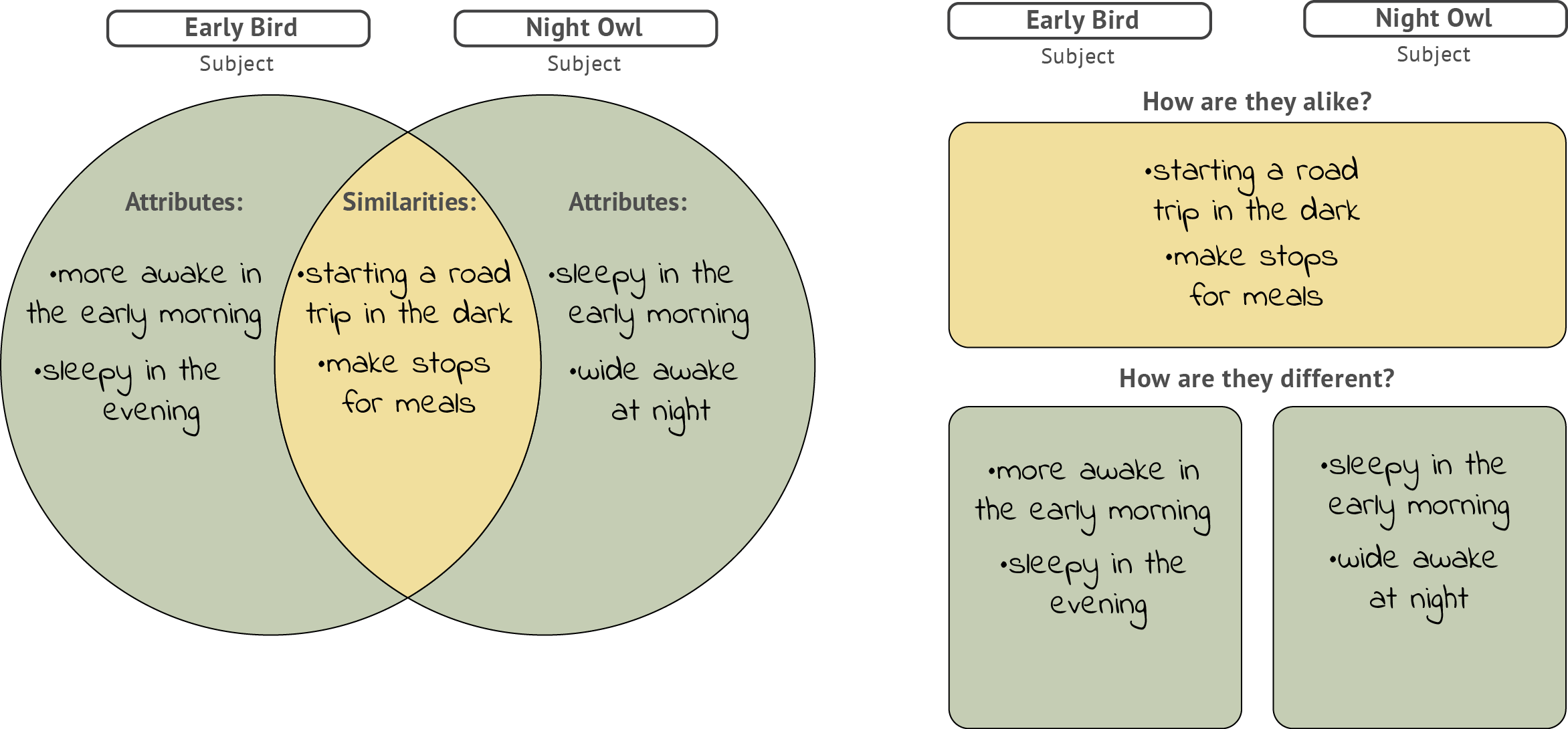

Comparison and Contrast to ExploreComparison and contrast is a wonderful method for thoroughly exploring complex issues. For example, human nature and human relationships are certainly complex. Leo Tolstoy is famous for exploring human nature. Tolstoy's novel Anna Karenina opens with the words, “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Here he makes an astute comparison between happy and unhappy families that is as profound as it is succinct. The benefit for comparing two complex ideas like this is that the reader can learn to appreciate each concept. Each subject is explained a little more by understanding both. The following is a paragraph that models how comparison and contrast can be used to explore. Depending on where the boundaries are drawn, the Southwest region of the United States is home to more than 25 different Native American tribes. Although the native people of the Southwest have some recent history in common, the tribes have different traditional heritages. A comparison of even two tribes currently living close by each other helps to underscore the profound variety of cultures among the tribes. For example, the Hopi Reservation is within the larger Navajo Nation, yet the languages, traditions, and art of the two peoples are very different. In this example, the reader comes to understand more about Native American tribes in general by a comparison of two tribes. If this were the introductory paragraph of an essay, the reader would expect to read specific examples of how the Hopi and the Navajo are different according to categories such as language, culture, heritage, history, and perhaps even diet and art. From a comparison that explores differences and similarities, a reader comes to learn more about these tribes and even understand the implied argument that other Southwestern tribes are also very different. Comparison and Contrast to PersuadeFinally, comparison and contrast essays are sometimes chosen as a way of persuading an audience to change their mind, or take a particular action in favor of or against something. In other words, it can be used to create a convincing argument. In this case, the author must make a calculated choice about which subjects to compare. For example, if you want to say that dried cherries are a healthy after school snack, you can show that, by comparison, cherries are a much healthier snack than cherry Pop Tarts. On the other hand, if you want to say that dried cherries are not a very good after school snack because they do not provide much protein, you can compare dried cherries to dried apricots, which have more protein. However, you have to be careful. If you compare what you want to promote with something that is obviously bad, you are committing a logical fallacy called using a Straw Man. When you use a Straw Man, you lose your reader’s respect and trust. For example, if you believe that enjoying a protein snack in the afternoon improves concentration while you study, comparing turkey and crackers to a Thanksgiving dinner is a Straw Man fallacy. A Thanksgiving dinner as an afternoon snack is probably a poor choice for many reasons. It is obviously the wrong choice for a snack (it is not even a snack!) and so it does not help to explain how or why the lighter protein snack is a good option in comparison. Your readers will know that you did not choose a subject for a fair comparison. Here is an example of how to use comparison and contrast to persuade. Starting out in the dark on an 8-hour road trip from Phoenix to Los Angeles is better for both early birds and night owls because it is cooler at night and there is less traffic. However, for both kinds of drivers, heading out at 4 a.m. is a better choice than starting out at 10 p.m. After an 8-hour drive, both drivers will be ready for breakfast and coffee. For the night owl, it will be 6 a.m. in Los Angeles when they arrive and very early for breakfast. The driver who started out at 4 a.m., though, will arrive in Los Angeles, just in time for lunch. Choosing Subjects to CompareWhen the right subjects are chosen to compare, a comparison and contrast essay almost writes itself. Although, as seen in previous examples, when students try to compare apples to oranges their essay’s purpose is unclear, and it is hard to make sense or add meaning to the topic. In addition, when the writer has a specific argument to make about a particular subject, the choice of what to use as a comparison is critical. Here are two templates (Template 1 / Template 2) you can use in your prewriting to help you figure out if you have two suitable subjects to compare. In each template, you choose two subjects. The words that describe the similar or different attributes can become points in your essay. As you fill in the templates, think about how the points might be grouped into categories that can help you organize your points into paragraphs.

The first is a classic Venn diagram, which you may already have seen in other classes. Each circle contains attributes of just one subject. The attributes in the space where the circles overlap is what the two subjects have in common. This second template is another way to view the same information. OrganizationDepending on the subject you choose to compare, the similarities may be remarkable and interesting. On the other hand, the contrasts may be the unexpected or interesting point you want to make. Comparison and contrast essays are not always split evenly between comparing and contrasting. Sometimes the comparison is obvious, such as comparing two styles of running shoes. The contrast is what is important in an essay comparing running shoes. Sometimes the similarities are the unexpected and interesting point we want to make. For example, a student might compare learning how to write with learning how to play baseball. These two skills seem so different; thus, the comparison of their similarities would be the more interesting and probably the longer part of an essay. The organization of a comparison and contrast essay is very important. In order to present a clear point of view and to help your reader follow your reasoning, comparison and contrast essays generally are organized in one of two ways. You may either alternate your points going back and forth between subjects in each paragraph, point-by-point, or you can choose to organize all your points about each subject one subject at a time in a series of paragraphs, subject-by-subject. Each organization results in a very different essay. Subject-by-SubjectAn essay using this method would spend a few paragraphs explaining all the points for the first subject and then spend the same number of paragraphs to explain all the points in the same order for the second subject. When choosing this organization, take into consideration whether your reader will be able to easily recall the early points about your first subject by the time you cover those similar categories for your second subject. This organization is good if you have fewer categories and want to explore each one in greater depth. The United States National Park Service (1926) used this method to compare and contrast the North rim to the South rim of the Grand Canyon. There is a remarkable difference between the north and south rims. The north rim, a thousand feet higher, is a colder country, clothed with thick lush forests of spruce, pine, fir, and quaking aspen, with no suggestions of the desert. Springs are found here; and deer are more plentiful than in any other area in the United States, as many as 1,000 having been counted along the auto road in one evening. It is a region soon to be used by hundreds of campers.

The views from the north rim are markedly different. One there sees close at hand the vast temples which form the background of the south rim view. One looks down upon them, and beyond them at the distant canyon floor and its gaping gorge with hides the river; and beyond these the south rim rises like a great streaked flat wall, and beyond that again, miles away, the dim blue San Francisco Peaks. It is certainly a spectacle full of sublimity and charm. There are those who, having seen both, consider it the greater. One of these was Dutton, whose description of the view from Point Sublime has become a classic. But there are many strenuous advocates of the superiority of the south rim view, which displays close at hand the detail of the mighty chasm of the Colorado, and views the monster temples at parade, far enough away to seem them in full perspective.

A five-paragraph essay is not recommended for this organization because it will take more than three body paragraphs to give each subject an equal discussion. If you spend two paragraphs on the first subject, you will need to spend two paragraphs on the second subject. The number of points you cover in each paragraph can also vary. Example of Subject-by-Subject Organization

You can use this template to organize comparison and contrast essays subject-by-subject Point-by-PointThis organizational method moves the reader’s attention back and forth between the subjects comparing points in each paragraph. The paragraphs are organized by categories. For example, an essay that compares the South and West rims of the Grand Canyon might have three body paragraphs that cover the topics, views, hiking trails, and lodging. All the points in each category are compared in each paragraph. Here is an example of a paragraph that compares two subjects (South and West Rims of the Grand Canyon) using one category (views) and two points (expansive versus narrow, and familiar versus unique). The South Rim views are the classic Grand Canyon views with which you are probably familiar. Wide, expansive, and panoramic—the Grand Canyon as seen from the South Rim is an almost surreal, unbelievable sight that will leave you changed forever. The view of the Grand Canyon from the West Rim is impressively deep, with narrower canyon walls plunging downward to the Colorado River below. Many visitors delight at the unique view of the Grand Canyon available only at the West Rim—the view from the Grand Canyon Skywalk. The view straight down through the glass cantilevered bridge offers a sometimes dizzying perspective on the Grand Canyon and the rocky chasm floor 4,000 feet down (Hecht, 2012, para. 7). Although the following template shows only two points for each paragraph, you can make your paragraphs longer by including more points of comparison. Example of Point-by-Point Organization:

An alternative way to think about organizing point-by-point is to highlight the similarities and differences in your organization. This is another style of point-by-point organization. Group the points in each paragraph by whether they explain a similarity or a difference. For example, within the category of views from the South and the West rims of the Grand Canyon, a writer can first explain how the views are similar and then explain how they are different. Critical-Thinking ApplicationsPersonal WritingComparison and contrast is a kind of method for organizing our thinking. As mentioned in the introduction, it is a helpful way to understand new concepts, and it is also a helpful way to make decisions. In your personal life, you might naturally compare a new kind of food to other foods you have had before, or you might realize that a new concept is something like another concept you already know. For example, your sister might tell you to meet her and your niece and nephew at a pizza and gaming parlor for dinner. When you text her back, you might ask, “Is the restaurant like Chuck E. Cheese?" Her reply is a micro compare and contrast argument: “Yes. Same thing only cheaper.” You use this strategy for more complicated issues as well. Applying for a loan to buy a home is very complicated. At some point in the process, you might notice that some of the steps remind you of getting a loan when you bought your car. In an instant, applying for a loan for a home becomes much more understandable. And finally, compare and contrast is an essential method for organizing information when it comes to making a decision. What career would you like to pursue? Will you continue to rent, or would you like to try to buy a home? There are very few decisions people make minute by minute and day by day that do not use this very sensible method for understanding the world. People use it to help them grow spiritually and intellectually. It is certainly worth your time to examine the process of comparison and contrast so you can become a more self-aware and better critical thinker. College WritingThe compare and contrast essay is a very popular tool for assessing how well a student understands a lesson. In order to answer a question that asks students to compare and contrast two periods in history, two famous people, two novels, two competing scientific hypotheses, two treatments for a medical disorder and so forth, students need to know each subject very well. Furthermore, students must be able to analyze each subject and apply their critical analysis in creative ways. Exercises that ask students to compare and contrast two subjects, test a more complex understanding of each subject and of how the world works than a question that asks students to summarize or explain a single subject. As a college student, expect to see comparison and contrast essay assignments, short-answer responses to test questions, and project assignments in any class you take for your program of study. Public/Civic/ProfessionalYou use comparison and contrast to create change in your public life. You use this method of organizing your ideas to improve products, and improve efficiency when you ask, “How can this be made better? How can this be done better?” You compare what you know to what you can only imagine. When you hope that changes will bring improvements, you compare and contrast bill proposals, candidates for office, and all manner of government plans. In this way you are engaging with your communities and becoming better global citizens. For example, when you watch a presidential debate, learning what each candidate thinks about the issues is only part of experience. You also use that information to weigh, evaluate, and judge the candidates against each other. In fact, the debaters often phrase their responses as comparison and contrast arguments. Comparison and contrast is a critical skill for creating and analyzing public discourse. For example, if your children’s elementary school is considering two possible fundraising projects for the band, you will want to make sure each plan is being compared on the same basis. For instance, you now know that you can decide if an argument claiming that selling chocolates raises more money than a car wash is a good comparison. You can ask how these two fundraisers are alike and how they are different. You might realize that the cost for buying chocolates to sell is a hurdle a car wash does not have to consider. ConclusionBecause you use comparisons all the time to make important decisions and to understand new information, it is worthwhile to look closely at how comparison and contrast works. In this chapter, you learned that it could be used incorrectly. When the subjects that are compared do not have enough in common, the comparison can be meaningless. Or, when comparison is used to persuade an audience that something is better than something else and one subject is obviously much worse, the comparison is not fair. You learned that it is helpful to understand metaphor, simile, and analogy in order to compare and contrast complex ideas in interesting ways. Finally, you also learned two ways to organize a comparison and contrast paragraph. If the subjects have only a few categories to compare, you can organize the paragraph subject-by-subject. But if there are many categories to compare, it is best to organize your paragraph point-by-point. ReferencesCovey, S. (1989). The 7 habits of highly effective people. (p. 47)New York, NY: Simon and Shuster. Hecht, C. (2012). Grand Canyon: South Rim or West Rim? Retrieved from http://ariztravel.com/2012/01/grand-canyon-south-rim-or-west-rim/ United States National Park Service. (1926) Circular of general information regarding Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona [Pamphlet] (p. 23). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. |