Before you begin reading this chapter, please take this quiz to see what you already know about the writing process.

IntroductionUsing the writing process allows you to become comfortable, organized, and satisfied with your writing. Writing, especially for writing assignments, can seem overwhelming for many students, but writing does not need to be intimidating. Instead, you can focus on one element of the process at a time to produce quality work that makes you proud. The writing process might be envisioned as a journey or an adventure. Writing takes time and effort, just like any other kind of journey. If the journey is by plane, time must be spent securing boarding passes, checking bags, conforming with security regulations, waiting in line to board and deplane, in addition to the time spent on the flight itself. If the journey is by car, time and resources must be invested in maintenance, pumping gas, and, of course, negotiating traffic. While these aspects of journeys are not always fun, the time invested in the writing process can be. First, it involves thinking critically. Thinking critically and developing ideas into well-written and well-structured pieces do not happen overnight. However, time spent on these processes can lead to exciting destinations. Instead of vacation spots like Hawaii or Paris, these destinations are ideas that the writer finds intriguing and valuable. People are busy, and they are always looking for ways to save time. That is why airlines can charge extra money for a fast line through security or a plane seat that affords quicker access off the plane, and, thus, out of the airport. While these shortcuts may be nice for those who can afford it, such passengers do not skip the lines or waiting entirely. It simply is not possible to travel by air without taking the time to follow the processes. The same is true of producing an effective piece of writing: Engaging with all steps of the writing process is a necessity. Sadly, though, the fact that writing takes time leads many writers to do what air travelers do not: They sometimes skip steps in the writing process. However, the writing process actually can save time for writers. Using all steps of the writing process is like buying that ticket to the quick line through airport security except that it costs you nothing but dedication. Think about it: How many writers have spent huge amounts of time staring at a blank sheet of paper or an empty computer screen? Writers who skip the steps in the writing process often develop what is known as writer’s block. This horrible feeling of knowing something must be written but not knowing what to write can be avoided by utilizing the steps of the writing process. The steps allow writers to think critically over a period of time to develop the best possible ideas. Then, writers are able to organize those ideas before writing, revising, and editing. In the end, this can save writers valuable time and lead to successful written work.

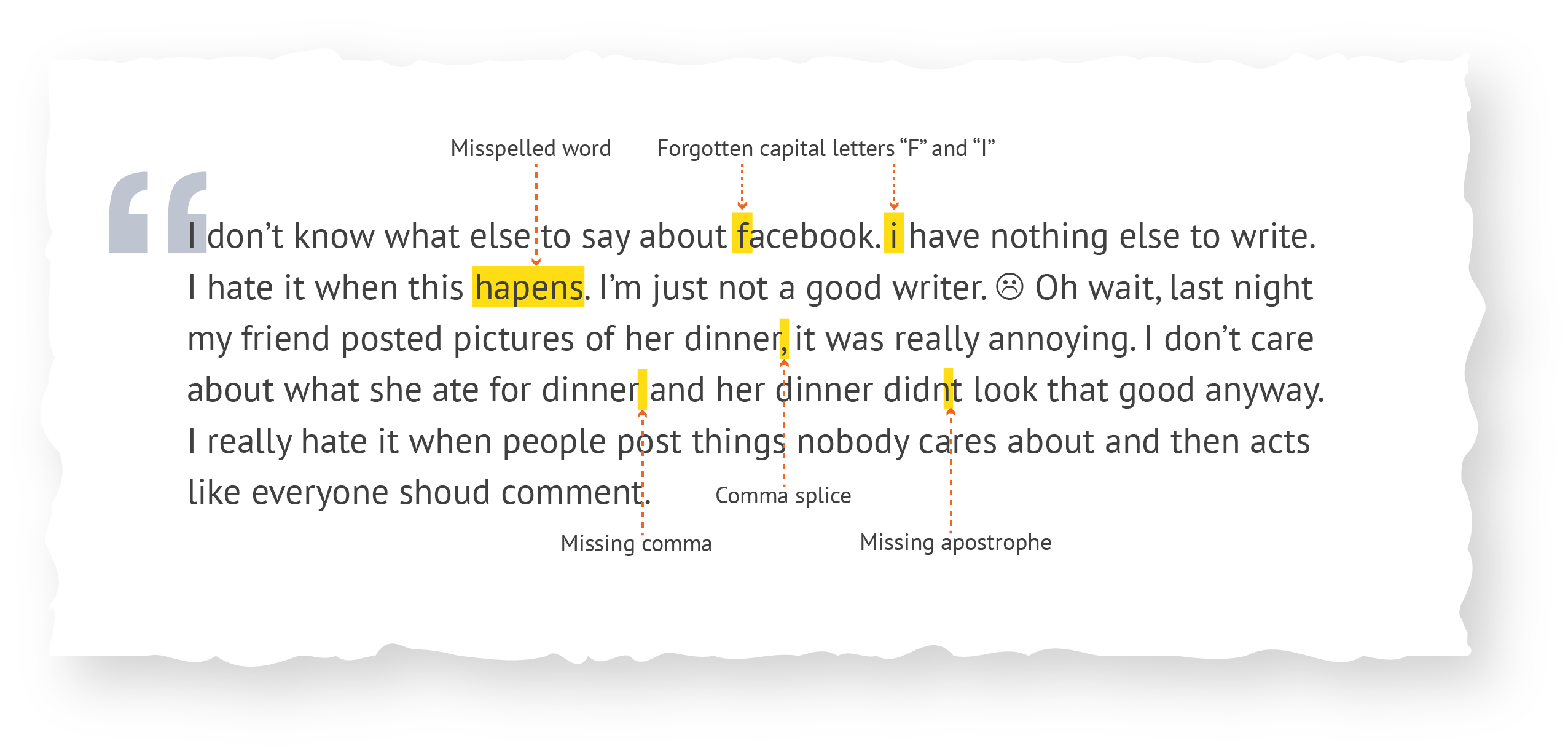

Imagine two families, each going on a road trip. One of the families might choose to organize the trip from beginning to end before they leave; the other family might choose to wing it, and make decisions as they go. The organized family will choose a destination and use GPS or a map to plan where they will stop for gas, food, and rest. They will also plan on how long the trip will take and how much it will cost. They set out on their journey knowing what to expect along the way and are prepared to arrive safely at their destination on time and ready for fun. The family that decides to wing it will do none of the above because they believe planning is a waste of time. Instead, they pile into the car without a plan of how they will get to their intended destination. They do not figure out where they will stop, and they pay no attention to how much the road trip necessities will cost. They might even run out of gas along the way because they are unaware of where the gas stations are located. Even if they are able to avoid running out of gas, they might run out of money because they were not prepared for the expenses involved in the trip. If they are lucky enough to refuel, eat, and rest without problems, they still run the risk of getting lost. One wrong turn can cost money and a substantial amount of time. Meanwhile, it is probable that this family would spend some time arguing, as the difficulties along the journey are likely to cause tension. It is possible this family would give up on the journey, and attempt to return home defeated. Or, this family might eventually arrive at their destination, but they would have very little time and money left to enjoy themselves, and the trip might seem like it was a waste of time. Sadly, they chose not to “waste time” planning, and in the end, the whole trip felt like wasted time. When writing, many people believe that winging it is faster, but the reality is that organizing not only leads to saved time, it leads to a better outcome. Utilizing the writing process allows writers to arrive at their destination—quality written work—without wasting time on wrong turns, frustration, or the urge to give up. Taking the time to use the writing process is worthwhile for writers; it leads them to their destination one step at a time. The writing process includes prewriting, drafting, revising, and editing. The prewriting process is cyclical, meaning that writers often repeat various steps in the writing process until they are satisfied with their work. PrewritingThe first, and lengthiest, step of the writing process is prewriting. During the prewriting process, writers determine their topics, audiences, and purposes, as well as develop their ideas by thinking critically as they prepare to write first drafts. Most of the difficult, critical thinking happens during the prewriting process. This way, the drafting process allows writers to focus on their writing instead of first developing their ideas. This is like the planning part of a road trip. During prewriting, writers make all of the necessary preparations to have successful pieces of writing, just like organized families going on road trips plan their journeys ahead of time to arrive at their destinations safely without any unexpected roadblocks. This section will offer five strategies for prewriting—freewriting, collaboration, brainstorming, questioning, clustering, and outlining—and will introduce four important considerations for any piece of writing. These four considerations—topic selection, scope, audience, and purpose—can become roadblocks if they are not addressed during the prewriting process. However, a little attention to topic selection, scope, audience, and purpose can turn a roadblock into a newly paved stretch of road. Key Considerations for the Writing ProcessTopic SelectionOftentimes, a writing assignment brings with it a set of topic choices, and sometimes selecting a topic can be a daunting step when the topic is very broad. Fortunately, writing assignments give little clues that can help a writer select a topic appropriate to the upcoming journey through the writing process. The assignment likely will give the writer a length requirement and objectives for the assignment. It may also provide a single topic or a list of topics from which the writer can choose. Whether there is a single topic or multiple topics, writers should give thought to what will be interesting to the reader and writer alike. Yes, the writer’s interests should be taken into consideration. Return to the notion of a road trip for a moment, and imagine a family that has taken many road trips to see the Grand Canyon. The first time it was awe-inspiring and beautiful. After that first time, however, it started to look like nothing more than a big hole in the ground. Now imagine that a member of that family has been asked to give input about the next road trip, which will also be to the Grand Canyon. The easiest, and perhaps most obvious, responses are to whine “not again!” or to say “okay.” However, with a little thought, that same member of the family might suggest a different approach this year: instead of looking at the Grand Canyon from the rim again, the family member might suggest taking a mule ride to the bottom, embarking on a helicopter tour, or spelunking in the caves near the Grand Canyon. Think of it: The same old road trip, but now it is brought to life again. Now there is the opportunity to experience some of the wonder and awe of the initial experience. It has become, in a word, interesting. What saved this year’s road trip from being dull and uninteresting? Well, it was the moment that the family member decided to put some thought into the destination and sought out new ways to envision that destination. The same strategy is useful for topic selection. Rather than choosing the easiest topic or most obvious approach to a topic, writers should take the time to think about how they can view their topic in a new way that will be interesting to them. ScopeChoosing a topic, whether based on a prompt or left up to the writer, is not the only element of topic selection. Once a writer chooses a topic, the writer must consider the scope of the writing project. Scope is the depth of the topic being covered. In other words, the writer must determine how broad or narrow the topic will be to decide whether or not the selected topic is appropriate for a particular writing assignment. The family road trip to the Grand Canyon might have been easily made interesting if the family members had the time and resources to travel out of state or widen the scope of their road trip. Likewise, if they had fewer resources, they might have limited their road trip to Prescott or Payson. Similarly, topics must be narrowed to meet shorter length requirements or broadened to meet lengthier requirements. For example, if a writer knows he or she must write a paper based on one to three problems with Facebook in 500-750 words, he or she will first need to determine one to three problems with Facebook. Perhaps the writer decides that three of the problems with Facebook are uninteresting posts, inappropriate posts, and argumentative posts. This writer will need to narrow the scope of this topic dramatically to write only 500-750 words. As is, this writer could probably write thousands upon thousands of words on these Facebook problems. For example, this writer would have to figure out all of the things that make Facebook posts uninteresting, and he or she would have to figure out all of the ways posts can be inappropriate or argumentative. It would take far more than 750 words to cover all of those things. Instead, this writer could narrow the topic down to something specific that could be covered fully within the allotted space. For example, this writer might choose to write about people who argue with their significant others on Facebook. Then, he or she would be ready to continue with the prewriting process using this topic. Audience and PurposeAnother way writers must consider the scope of their topics is by determining who is in their intended audience and the purpose or reason readers should read the piece of writing. Remember, almost all writing (with the exception of journal writing) should have an intended audience that benefits in some way from reading. Remember, writers must make sure they provide readers with material that is useful, interesting, and engaging, or readers might choose not to read. This means that writers need to provide information, examples, and arguments that impact readers in meaningful ways and encourage them to continue reading. If writers do not determine their intended audiences, they cannot be sure the writing will affect the readers. This does not mean that the same topic could not be presented to multiple groups of intended audiences. For example, a paper in which a writer examines the problems that arise from Facebook posts could have an impact on many different groups of people, including teenagers, college students, parents, college personnel, and coworkers. While there is potential for a paper on this topic to be meaningful for all of these groups of people, it is unlikely that a writer will be able to address each of these groups in one paper. Because of this, writers must choose intended audiences to focus their writing. Also, remember that while writers must choose intended audiences to focus their writing, this does not mean that those outside of the intended audiences cannot read the work. Think about movies or television shows. All movies and television shows have intended audiences, but that does not mean that others cannot enjoy the programs. For example, movies that target young children are often enjoyed by people of all ages. That does not change the fact that the movies were created to entertain children in particular. Often, writers forget to choose an intended audience and/or a purpose, and this leads to significant difficulties throughout the writing process. For example, if a writer chooses to write a 500-750-word paper on the problems that arise from arguing with significant others via Facebook posts, but does not choose an intended audience or a purpose, what will he or she write? Chances are, this writer will write very general complaints about arguing with significant others on Facebook. The writer will not know which types of examples or evidence to use because he or she will not know whether to address this problem as it relates to college students, coworkers, parents, etc. The writer also will not know what he or she expects from the readers. For example, does the writer just want readers to be aware of the problems that arise with Facebook arguments, or does the writer want readers to change their behavior when it comes to Facebook posts? These choices must be made for the writer to achieve a goal with the piece of writing. Also, making these choices immediately simplifies the writer’s job, as he or she is able to focus particularly on the way the problem relates to one group of people. For example, if this writer chooses to focus on the problems with college students arguing on Facebook with the purpose of convincing college students to stop arguing on Facebook, the writer has a clear vision of the goal for writing the piece. With an intended audience identified, the writer should now have a much clearer picture of what needs to be written to convince college students to change this behavior; in addition, the writer should have a good idea of what to avoid discussing to maintain the readers’ attention. To choose a topic, writers must determine the scope, audience, and purpose. To think critically to develop ideas, writers use additional elements of the prewriting process. The following prewriting strategies can be used one at a time or together, and they should be repeated until the writer is satisfied with all of his or her ideas. Six Prewriting StrategiesFreewritingOne of the best ways to begin the prewriting process is freewriting. Freewriting, at its core, is writing anything and everything that comes to mind without stopping for a particular period of time, usually about 3 to 5 minutes. Focused freewriting is freewriting on a particular topic or group of topic options or freewriting in response to a prompt. Freewriting is a wonderful way for writers to use a short amount of time to prepare for the more difficult critical thinking to come. Freewriting is a time of no judgment. Often, writers get in their own way when they write because they fear judgment. They worry about what others will think of their ideas, and they worry about their grammar, punctuation, and spelling. During the freewriting process, writers should never worry about these things. Freewriting does not involve proofreading, the process of checking for errors in grammar, punctuation, or spelling. Freewriting is one way writers can escape from the fear of judgment by allowing themselves the freedom to express their thoughts without repercussions. This escape often helps writers feel calmer, which can lead them to develop wonderful ideas. During the focused freewriting process, writers write anything that comes to mind about their topics until time is up. If writers suddenly find themselves running out of things to write, they should not stop, but, instead, they should write about their lack of ideas until they have new ideas. For example, a writer might be asked to write about potential problems with Facebook. If that writer runs out of things to write, he or she might write:

Notice that in the above example the writer wrote about his or her frustration until a new idea surfaced. Also, notice that the writer made several grammar, punctuation, and spelling errors, but the writer did not stop to correct the errors. That is a good thing during prewriting! By writing without stopping, the writer eventually thought of something to say that might lead to a meaningful piece of writing about a problem with Facebook. Initially, the writer felt insecure, but the writer ended up writing briefly about people who make uninteresting posts on Facebook and expect comments in response. This might be a great topic to continue using for the assignment.

All three of these potential outcomes are valuable. It is important to remember that in 3 to 5 minutes, writers might come up with interesting ideas to develop, or at least they can eliminate the confusion and jumbled ideas from their minds to enter into the critical-thinking parts of the writing process. Also, at any point in the prewriting process, additional freewrites might help writers focus on the task at hand. In fact, sometimes, writers can have success discovering or developing ideas by doing looped freewriting in which, after completing one freewrite, a writer circles the one or two best ideas, and freewrites on those ideas. Looped freewriting can be especially useful when working on topic selection and scope. However, freewriting and looped freewriting can be used at any stage in the writing process and can be useful in overcoming the dreaded writer’s block. CollaborationWhile many people consider writing to be a solo activity, many elements of the writing process involve working with others to inspire, share, and evaluate new ideas. This is why it is important for every writer to become a member of a writing community. A writing community is a group of writers who work together to achieve the best final products. They discuss ideas, work together to choose the best ideas and solidify writing plans, and evaluate and provide feedback on drafts after they have been written. Collaboration is one of the most effective tools writers can utilize as they work through the writing process. After freewriting, all of the other prewriting strategies can be used while collaborating with members of a writer’s writing community. BrainstormingBrainstorming is a time for writers to think critically and list all of the ideas they have about a topic. It is always a good idea to write down every possibility; later, writers are free to eliminate items from brainstorming lists when they organize their ideas. Remember, too many ideas are better than too few ideas. Often, the first few ideas in a brainstorming list are the most obvious or generic. Those are often the ideas writers should eliminate or touch on briefly in the writing, as their readers are likely to be hoping to gain new information or arguments from what they read. For example, if a writer is brainstorming about why college students should not argue on Facebook, he or she might make a brainstorming list that looks something like this:

This writer might realize that “Annoying to friends/family” and “Uncomfortable for those not involved” are somewhat obvious, and should be mentioned only briefly. Instead, this writer might choose to focus on the ways other people become involved in the arguments when they are posted online. This writer might choose to develop a more specific brainstorming list based on why the involvement of others can make arguments worse, be embarrassing, and create new arguments. Each time the writer focuses on a particular element of the topic, he or she should add to the brainstorming list or write additional lists. The more detailed the brainstorming list becomes, the easier the writing process will be. Remember, brainstorming does not mean merely writing down the first few ideas that come into the writer’s mind. Instead, brainstorming requires writers to think critically and search for meaningful and interesting points to make in a piece of writing. QuestioningQuestioning is a great way to help writers think more critically about their topics. Writers can question themselves, or they can work with partners to discuss the answers to questions. Writers should always ask themselves (or be asked):

The tricky part is that asking most of these questions only one time will not result in critically thought out ideas. Instead, questions like “Why?” and “How?” should be asked repeatedly to allow writers to explore their topics fully. For example, if a writer says that arguing on Facebook creates new arguments, it would be wise to ask the writer why that happens. The writer might answer, “because everyone gets involved and comments on the argument.” Some writers might stop here, but that would be a mistake. Instead, the writer should figure out why this causes new arguments. He or she might determine that people become upset when their friends or family members take sides on the argument, or he or she might suggest that some of the comments might seem harsh or mean. If the writer keeps trying to figure out why this happens, he or she has a good chance of explaining this to readers in the writing. All of the explanations should be included in the brainstorming list. ClusteringClustering is the same as brainstorming and questioning, but it is done in a visual manner that helps writers see the ideas and their relationships to each other. The writer draws a circle in the middle of a page and writes the topic in the center. Then, the writer draws lines to new circles with additional ideas. Take a look at this cluster on the same Facebook topic. OutliningOnce writers have done all of the necessary prewriting to develop their ideas, writers should outline their material in the order they plan to present it in the draft. Many people dislike outlines because they think outlines take too much time. In reality, outlines not only result in high-quality drafts, but outlines also save writers valuable time. Think back to the road trip discussed previously. If the organized family had a list of all of the places they wanted to stop but didn’t create a plan of how they would get from place to place, they might still encounter many of the difficulties the family that decided to wing it would face. Instead, the organized family needed to plot out the order of the trip, including everything they wanted to do, ahead of time. This is very much like an outline that contains a full plan for the first draft. Outlines can take many different forms. If a particular outline format is not assigned, writers should still create outlines; however, writers should outline in the format that seems the most helpful. The most important thing about an outline is that it is detailed enough to provide writers with all of the material that must be included in the draft in the appropriate order to guide readers through the ideas presented. Outlines do not need to include complete sentences; however, they do need to include complete ideas. This way, writers do not need to think about developing their ideas when they create their first drafts. Instead, they only need to focus on style and tone when they write their drafts because they already did all of the necessary critical thinking. Remember, it is extremely difficult for writers to think about everything at the same time and still produce quality work when writers focus on one element at a time, they actually save time and produce quality work. The following is an example of one way to write a detailed outline for a stand-alone paragraph:

DraftingOnce writers have created detailed outlines, they are ready to begin the drafting process. Because all of the critical thinking and organizing were completed during the prewriting process, at this point, writers need to turn the ideas mentioned in the outline into complete sentences that flow together well with a consistent and appropriate style and tone. When writers use their detailed outlines to create first drafts, they will find that drafting is much easier than it is without outlines. Revising ContentAfter a first draft has been written, the next step is revising the content. Even though writers work carefully through the prewriting and drafting processes, revisions are almost always necessary to produce the highest quality work possible. When revising content, writers look for any material that is missing or requires explanations, support, or examples. They also look for material in the draft that seems out of place, confusing, or unnecessary. During content revision, writers do not worry about grammar, punctuation, or spelling These things are addressed during the editing process. Instead, writers focus on changes that must be made regarding content and organization. It would be a waste of time for a writer to work on making a sentence grammatically correct and properly punctuated if the idea in the sentence needed to be eliminated from the piece of writing. Waiting to edit until after the content revision occurs saves writers time because they don’t try to solve problems with sentences that might be revised or eliminated anyway. Remember, when writers focus on one element at a time, they are more likely to produce quality written work. One of the best ways to revise content is to ask questions (similar to questioning during prewriting). Here, several general questions that can be asked about any writing assignment are included. Always make sure to add specific questions based on assignment requirements as needed. At the very least, use the answers to the following questions to revise paragraphs and essays.

Peer ReviewsNot only should writers ask and answer questions about their own drafts, but they should also consult others to get additional answers to the questions. Remember, writers know what they intend to say when they write material in drafts, but readers sometimes will not understand what writers mean. It is extremely important to work with at least one partner from a writer’s writing community during the revision process to find out how someone other than the writer interprets the material; this is known as peer review. When done as part of a class activity, sometimes specific peer-review questions will be provided. When questions are not provided, always ask peer reviewers to answer the questions outlined above, and develop additional questions based on assignment directions. When giving and receiving peer reviews, everyone involved should be as honest as possible. Genuine feedback is required to help writers revise content to create high-quality work. Peer reviewers should always give both compliments and constructive criticism with specific suggestions, and writers should not take constructive criticism and suggestions personally. Also, remember that writers are not required to implement the suggestions peer reviewers make. Ultimately, each writer is responsible for his or her paper, so the writer must make decisions about which pieces of advice will be used. EditingAfter writers are satisfied with the content in their drafts, it is time to begin the editing process. Editing consists of correcting sentence-level errors, including grammar, punctuation, spelling, and word choice errors, in addition to ensuring the fluidity of sentences and paragraphs. Editing can be a time-consuming process, but writers must remember how important it is to use appropriate language and conventions to achieve their purposes for their readers. All of the corrections that occur during editing help readers understand the important content writers are trying to express. If errors interrupt a reader’s experience while reading, he or she is likely to become confused and frustrated, and often, not only will the reader lose trust in the writer’s expertise, but also the reader is likely to stop reading. Because of this, it is worthwhile for writers to edit carefully to make sure readers understand and appreciate the content in the work. Editing Out LoudTo catch and correct the most errors, editing should be done out loud. The best way to edit is to read each sentence out loud, and stop to make any necessary corrections before moving on to the next sentence. Writers must use their eyes to see errors, but they should also use their ears to hear errors their eyes might miss. Often, when people quickly scan material for errors, their brains fill in the missing or incorrect elements without the writer consciously realizing it happened. When writers read their work out loud, they often stumble over words or have trouble reading; this is usually because there is an error in the sentence. When writers use their eyes and ears to edit, they find more errors. Once writers find their errors, they are able to use their skills to correct the errors. Collaborative EditingIt is always a great idea for writers to collaborate with at least one member of their writing community during the editing process. Each writer has different strengths and weaknesses, especially when it comes to sentence-level errors. For example, a writing community may have one member who struggles with comma splices, but another member, who has no difficulties with comma splices, struggles with word choice. If these writers work together during editing, they will be able to take advantage of their individual strengths and weaknesses, and they will be able to help each other edit effectively. Still, each writer is responsible for the final editing decisions about his or her work. Partners should always make suggestions, but the changes should always be made by the writer accountable for the final product. Once editing is completed, the piece of writing is ready for readers. FeedbackThe writing process seems to be over once an audience is invited to read a written work, but there is always room for more critical thought and improvement. When readers have access to a piece of writing, they often have responses and/or suggestions that writers should consider. Sometimes, writers are able to revise again based on the feedback they receive. However, even when future revisions are not requested, writers have an incredible learning opportunity every time they receive feedback. When writers pay careful attention to what readers have to say about what they read, writers can continue to improve their writing for future projects. Think back to the example of a family taking a road trip. While on the journey, the family might learn of a short cut they could have taken to have arrived at their destination sooner. While they were unable to use the short cut during this trip, they will store that information for future trips to the same place. In much the same way, writers can use feedback from readers to improve their future written work; whereas, ignoring feedback will lead writers to make the same mistakes again, which hinders improvement. Because writers should always try to build on their writing abilities, they should welcome feedback and learn from their readers. Remember, writers should thoughtfully consider feedback given at any time during the writing process to continue learning, improving, and succeeding. SummaryUsing the writing process when you write saves time. Focusing on one part of the writing process at a time also makes writing easier and less frustrating. The writing process includes prewriting (focused freewriting, brainstorming, questioning, clustering, choosing an intended audience, choosing an appropriate scope, and outlining), drafting, revising content, editing, and learning from feedback. The more you practice using the writing process, whether for personal, professional, or academic writing, the better your final products will become. Critical-Thinking ApplicationsThe journey you take through the writing process for UNV-100 is not an isolated, stand-alone journey. Instead, it is a process that can be used for all writing journeys. Certainly, the writing process will be helpful in UNV-100; however, it will also be useful in your other classes, whether your assignment is to write a discussion question response or an essay. In fact, with a little critical thinking, people can find the writing process useful outside of college as well. It can be used in the professional world when writing a report for a supervisor, an email, or even a job application. Even personal writing, like diaries, journals, and blogs can benefit from the writing process. Take a few minutes to brainstorm where you can benefit from using the writing process now and in the future, and remember: The journey is just as important as the destination. |