Before you begin reading this chapter, please take this quiz to see what you already know about essays.

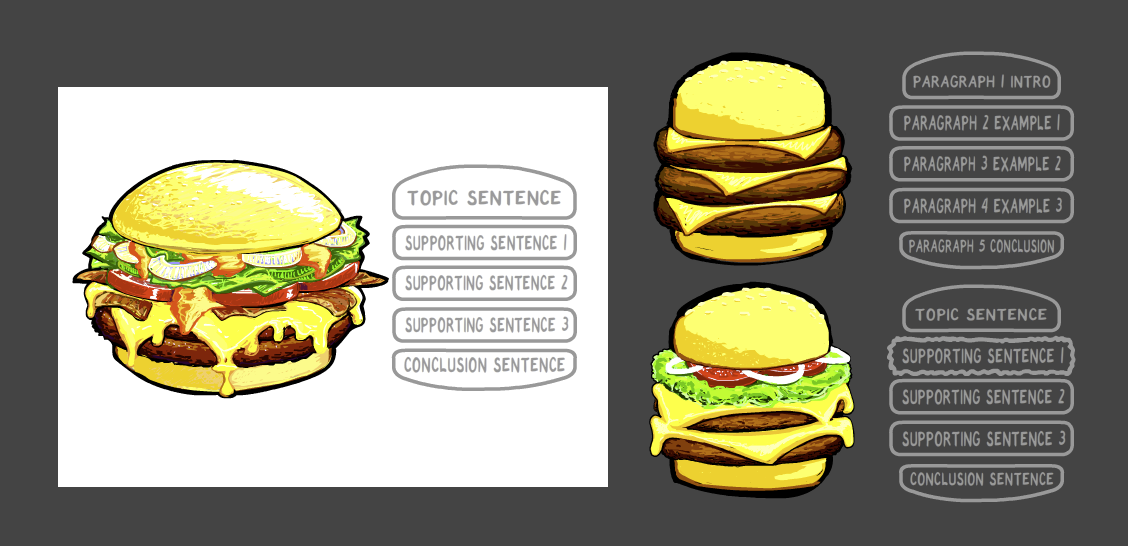

IntroductionHow many times have you heard that life is a journey? Well, consider for a moment that, because the message you deliver takes your audience from Point A to Point B, verbal and written communication is a journey of sorts. The essay is one vehicle that can help you make that journey. Purpose of Academic EssaysWhen planning a trip, it is important to know why you are making the trip in the first place. Is it to deliver an important package, or is it a road trip with friends? The answer to this question will have an impact on whether you pack a suitcase, what you pack, and the route you take. Whenever you plan to write an essay, make sure you have a clear purpose in mind. If you do not know why you are writing, neither will your reader. Without knowing your destination, how will you know when you have arrived? Scholars write academic essays for as many reasons as one might get into a car, put the key in the ignition, and drive. A scholar’s writing will stem from his or her purpose. Is it to propose that the university add more parking spaces on campus for commuter students? Is it to persuade fellow students to vote for a particular candidate for student government? Is it to inform fellow students of how a particular piece of local legislation might affect them? There are many reasons why a scholar might write an essay, but, generally, these reasons could be grouped into three main categories: to inform and/or persuade readers; to apply and synthesize concepts, information, and ideas; and to activate prior knowledge with a connection to new knowledge. Inform and/or Persuade ReadersPresenting facts in an organized manner to inform readers is one of the most basic and common writing purposes. This is often initiated from an instructor’s request to present material you have learned in the form of an essay exam or research paper. Such assignments help the instructor determine whether or not students have mastered the material in class. Persuasion is often a part of informative essay writing, and involves aligning facts and support to convince a reader of a particular view on a debatable topic. Apply and Synthesize Concepts, Information, and IdeasAcademic writers often gather information and research from a variety of sources in order to arrive at new conclusions. This type of writing relies heavily on the writer’s ability to infer relationships among ideas and concepts successfully, synthesize information from a number of sources, and to produce a meaningful conclusion for the reader. This happens most often when you research a particular topic and report on that topic using your own words and in your own way. Activate Prior Knowledge with a Connection to New KnowledgeEssays often help readers to make connections between prior knowledge and new concepts. This type of writing truly brings the reader from Point A to Point B using preexisting stepping stones to make the journey. You activate prior knowledge all day long in everything you do. For example, you might set out on a day trip to a destination you have never visited before. Every time you undertake such a journey, you do not need to relearn how to drive a car, or how to drive down your street in order to get on the highway that leads to that new destination. You already possess that knowledge, and you automatically make that connection between what you already know, and what you are about to learn. The same thing happens when you read and learn new concepts. You form connections between old and new concepts. The Academic Essay vs. the Five-Paragraph EssayAn academic essay can come in many forms. The five-paragraph essay is only one type of academic writing, and it is often the first type of essay structure that a writing student learns because of its basic nature. The five-paragraph essay, if planned correctly, will always get readers to their destination in the most straightforward manner possible. The five-paragraph essay is made up of three main parts: the introductory paragraph, three supporting paragraphs, and the concluding paragraph. Academic essays may expand on this basic form, and break out of the constricting five-paragraph structure. As you advance in your classes, you will be expected to include as many paragraphs in your essay as the assignment calls for, but all essays, no matter how long, will always retain the same basic elements: an introduction, supporting paragraphs, and a conclusion. Patterns of OrganizationSo you want to head south of the border to Mexico to have some fun on the beach? Before you start planning your vacation days, you should decide on your mode of transportation. Should you plan to take a plane, a cruise ship, or a good old-fashioned road trip? The method of transportation you choose will affect the experience of your trip. Will the views from your window be clouds, waves, and dolphins or desert and cacti? Will the food you enjoy during the trip be peanuts and ginger ale, open-air seafood buffets, or sausage gravy-covered biscuits and cowboy coffee at roadside diners? As the writer, you decide what the experience will be for your reader. Here are just a few of the options when it comes to patterns of organization for your essay: ArgumentationArgumentation essays refer not to actual arguments, but to a focused, organized presentation in essay format that presents a particular viewpoint on a debatable topic. The essay should be presented in a clear, authoritative tone with plenty of support, regardless of whether the topic is the student's choice or assigned by an instructor. Examples of written arguments may be in the form of op-ed articles in the newspaper, letters attached to petitions, or essays written in favor of or against any debatable topic. Causal AnalysisCausal analysis is exactly what it sounds like—an analysis of the cause, and sometimes the effects, of a condition, event, or situation. We deal with causes and effects every day. If we do not put gas in our car, it eventually will sputter and die on the side of the road. If we do not use a roadmap or GPS, the effect might be that we do not reach our desired destination. Writing a causal analysis essay is about making concrete connections between events, and expressing them in a logical, ordered manner in written form for the reader. ClassificationClassification essays strive to make order or sense of items, people, objects, or data by grouping them in categories that make sense and will help the reader to reach greater understanding about those entities. For example, vehicles can be grouped into cars, SUVs, vans, and pickups. Vehicles may also be classified by number of cylinders in the engine, or the fact that the vehicle is either domestic or foreign. Division is often mentioned in the same breath as classification because it serves the same purpose: The writer divides or separates a large subject into divisible parts. For instance, the field of transportation can be separated into types of transportation such as road, air, and sea. In both cases, the writer is doing what humans love to do: categorizing, labeling, and dividing into groups in order to make sense of information. Compare/ContrastWriting a compare/contrast essay is an exercise in examining similarities and differences. This may seem complicated at first, but this is actually something you do from the moment you wake up until the moment you go to sleep. Should you take your new designer travel bag or your vintage suitcase on your road trip? You may compare and contrast their size, durability, and visual appeal in order to arrive at your decision. Should you take the southern or northern route when you take your cross-country road trip? You may want to compare and contrast routes according to total miles, current weather, and available rest stops along each route. DefinitionYou would have to search far and wide to find someone who had never read a dictionary definition. Most people are familiar with formal definitions in dictionaries in which each entry lists the term being defined, the class or group to which the term belongs, and the characteristics that differentiate it from others in its class. It is short, concise, and helps the reader understand what the term means using just a line or two. According to Merriam-Webster, a road trip is “a long trip in a car, truck, etc.” (2014); however, there are many ways in which a writer could expand upon this definition. If you took the “road trip of a lifetime” with your best friends, you might want to write an entire essay to properly define what a road trip is from your perspective. A lengthier, detailed description is sometimes called an extended definition. ExemplificationExemplification essays illuminate a subject by telling the reader what that subject is or isn’t by using examples. This pattern almost always overlaps with another pattern of organization. Many essays will toss in a few examples to highlight the subject, so when trying to distinguish a distinct pattern of organization, you might have a difficult time deciding whether an essay is an exemplification, narrative, definition, or some other essay pattern. You do not have to choose just one. Chances are it could be classified as more than one pattern of organization. This chapter on essays could serve as an example of exemplification. The chapter provides a number of examples of types of essays (including argumentation, causal analysis, classification, and so on) in order to define the essence of the essay. NarrativeA Narrative is an organized sequence of events, real or imagined, that relates a story that makes a point. For many years people have used verbal and written narratives to pass on stories from one generation to the next. Narratives spark interest, provide entertainment, offer instruction, and provide insight into shared human experiences. They are an important part of writing in college, and in life in general. The narrative pattern is often the most comfortable for writers, as everyone has told a story before, either at a party, a family dinner, or to a group of friends. Parts of Academic EssaysBefore taking a road trip, it is a good idea to know the basic parts of your vehicle, as you will depend on it to take you to your destination. Where do you put the gas when it is time to fill up? How do you turn on the windshield wipers when it starts to rain? Where is the trunk to store your luggage? Just as it is important to know the basic parts of your vehicle, it is important to know the basic parts of your essay. Introduction and ThesisThe introduction of an essay has a very basic, but critical purpose. It is perhaps the most important part of the entire essay. Generally, the introduction does three things:

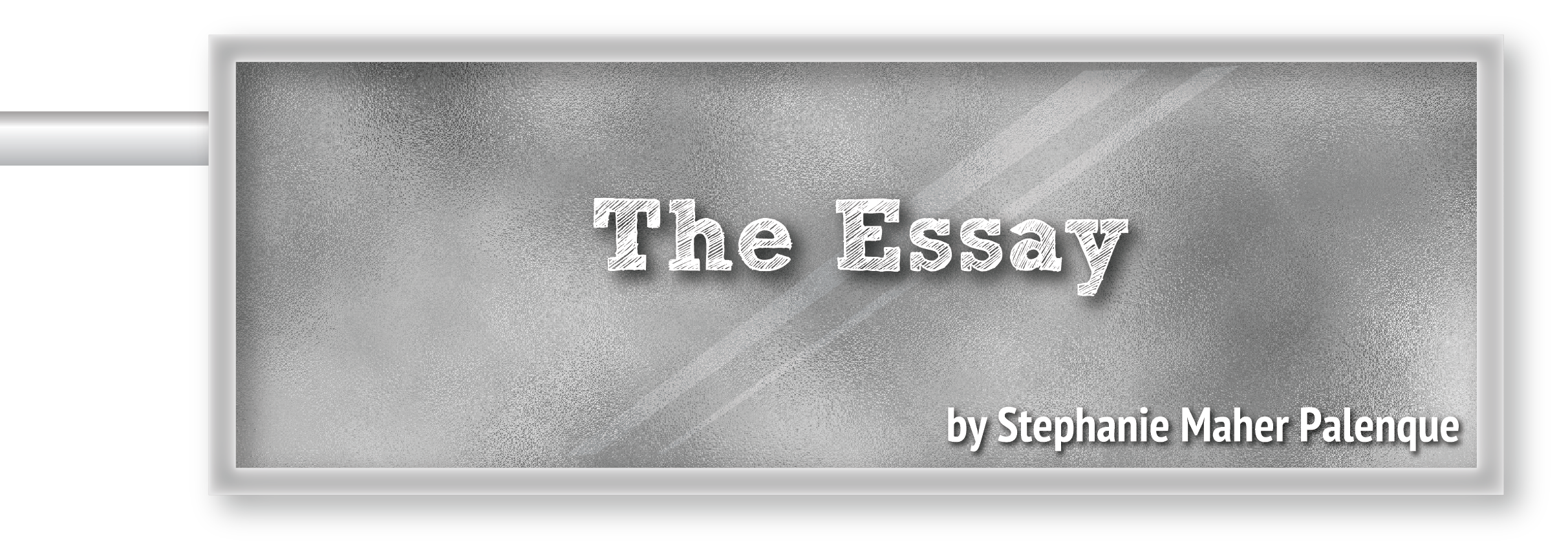

Ideally, the essay’s thesis will be the last sentence of the first paragraph of the introduction. It is a strong, arguable statement that provides a blueprint for the reader to follow. Often, you will hear of a thesis, which lists talking points or main topics that the essay will cover. This helps to provide structure for the rest of the essay. Body ParagraphsThe paragraphs that support the structure of the essay are called the body paragraphs. Each one of these paragraphs supports the argument in the thesis statement. Each body paragraph will have its own structure, including a topic sentence statement, supporting sentences, and a concluding sentence.  Conclusion

Conclusion

The conclusion is perhaps the most misunderstood part of the essay. As the name indicates, its placement is at the end of the essay, and it is made up of the last paragraph or paragraphs in the essay. The conclusion wraps up the writer’s point or points and leaves the reader with a satisfying close. It hearkens back to the introduction, but does not repeat or restate it. Transitions within Academic EssaysAn essay without transitions is like a road trip without interstates, bridges, roundabouts, or exit ramps. A traveler might eventually get to where he or she is going, but not very smoothly or efficiently. A writer will make multiple points throughout an essay, and transitions serve as the glue that holds the essay together and help the writer move smoothly and logically from one point to the next. Transitions are words, phrases, or sentences that guide the reader from one thought to the next in a logical, organized, and seamless train of thought. Have you ever traveled to a place that looked totally unfamiliar, and you not only wondered how you got there, but also if you were even in the right place? Without including transitions in your essay, your reader might feel the same way. Using Transitions to Guide ReadersTransitions should be as natural as possible. The reader should not notice your transitions; rather, your reader should consider the points you have made throughout your essay. There is more than one technique for transition writing, and it is up to the attentive, careful writer to ensure that new ideas are not dropped on the reader without a logical transition from one thought to the next. Strategies for TransitionsSome of the techniques a writer can use include repetition, transitional words and phrases, transitional questions, and bridging sentences. RepetitionParagraphs may be linked by a word or phrase that is repeated at the start of each new paragraph. This not only signals to the reader that there will be a different point made in the next paragraphs, but also it provides some continuity and uniformity throughout. Ideally, the word or phrase should be a point that you are trying to drive home to the reader. The following is an excellent example of repetition. The author, Judy Brady, drives home her political, and at that time controversial and progressive, point through repetition of the phrase “I want a wife” throughout the essay. I want a wife who will not bother me with rambling complaints about awife's duties. But I want a wife who will listen to me when I feel the need to explain a rather difficult point I have come across in my course studies. And I want a wife who will type my papers for me when I have written them. I want a wife who will take care of the details of my social life. When my wife and I are invited out by my friends, I want a wife who will take care of the baby-sitting arrangements. When I meet people at school that I like and want to entertain, I want a wife who will have the house clean, will prepare a special meal, serve it to me and my friends, and not interrupt when I talk about things that interest me and my friends. I want a wife who will have arranged that the children are fed and ready for bed before my guests arrive so that the children do not bother us. I want a wife who takes care of the needs of my guests so that they feel comfortable, who makes sure that they have an ashtray, that they are passed the hors d'oeuvres, that they are offered a second helping of the food, that their wine glasses are replenished when necessary, that their coffee is served to them as they like it. And I want a wife who knows that sometimes I need a night out by myself (Brady, 1971). Transitional Words and Phrases There are many phrases that signal transition to the reader, without having to overwork the point that a transition is being made from one subject or thought to the next. Some of these include: on the other hand, to this end, moreover, furthermore, first, second, and third, in conclusion, etc. In addition to being a printer, political theorist, politician, scientist, inventor, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat, Benjamin Franklin was also a prolific writer. Franklin mastered the art of expressing himself and his ideas through words. Read the following excerpt and take note of how seamlessly he uses transitional words and phrases. As a great part of our life is spent in sleep, during which we have sometimes pleasant and sometimes painful dreams, it becomes of some consequence to obtain the one kind and avoid the other; for whether real or imaginary, pain is pain and pleasure is pleasure. If we can sleep without dreaming, it is well that painful dreams are avoided. If, while we sleep, we can have any pleasant dreams, it is, as the French say, autant de gagné, so much added to the pleasure of life.

Transitional Questions Asking a question that readers might ask, essentially, takes the readers by the hand and mentally leads them to where you want them to go, instead of waiting and hoping that they make the transition on their own. Grace Rhys, an Irish poet, novelist, and essayist, uses transitional questions effectively in this example. She draws thoughtful comparisons between humans and pigs, and through her strategic transitional questions encourages her readers to do the same. He is dirty, people say. Nay, is he as dirty (or, at least, as complicated in his dirt) as his brother man can be? Let those who know the dens of London give the answer. Leave the pig to himself, and he is not so bad. He knows his mother mud is cleansing; he rolls partly because he loves her and partly because he wishes to be clean. Bridging Sentences A bridging sentence effectively sums up what came before and foreshadows or anticipates what will transpire in the next sentences. Sir Alan Patrick Herbert was a member of Parliament as well as a writer who published volumes of humorous poems and essays. His writing on the bathroom works is bridged at the beginning of the next sentence to transition to his points on smoking. But the most extraordinary thing about the modern bath is that there is no provision for shaving in it. Shaving in the bath I regard as the last word in systematic luxury. But in the ordinary bath it is very difficult. There is nowhere to put anything. There ought to be a kind of shaving tray attached to every bath, which you could swing in on a flexible arm, complete with mirror and soap and strop, new blades and shaving-papers and all the other confounded paraphernalia. Then, I think, shaving would be almost tolerable, and there wouldn't be so many of these horrible beards about. Critical-Thinking ApplicationsWriting as a Global CitizenNow, that you can communicate with people on the other side of the globe in an instant in a variety of ways, one way in which you can become an engaged, effective global citizen is through writing. Do you see a policy that needs to be addressed at the university? Write an editorial for your university newspaper or blog. Do you feel strongly about a local law? Write a letter to your congressperson. Do you want to bring local awareness to a serious global issue? Post about it on the Internet. The power of the pen (or the keyboard) can be critical and produces significant change in our society. College WritingAs a student, you will express yourself most often through writing. You will write research papers, essays, scholarly articles, and even letters to your professors. Your points will be made most effective through sharp writing skills. Professional WritingWriting isn’t limited to your college years. For the rest of your life you will use your writing skills for workplace proposals, presentations, and even emails to your colleagues. You always will want to make a positive impression on workplace superiors, prospective employers, and coworkers, even in emails and memos. Your intellect and business acumen will often be judged, at least in part, by your writing skills. Personal WritingWriting has long been considered a therapeutic activity. Writing allows the writer to figure out situations in life that may be confusing or call for intense reflection. Humans have a strong desire to know themselves, and to be known and understood by others. Writing plays a critical part in this process of making personal connections with ourselves and others. People have passed down stories from one generation to another through the printed word. Essay writing serves as a formal, organized way to put your thoughts on paper, when those thoughts might not start out as formal or organized at all. Many may think of personal writing as unstructured; however, in order for writing to be effective, it must have some sense of organization and structure. Personal writing is an art, like any other type of art. As a student, you will want to master that art. ConclusionAs a student and a writer, you will want to have as many tools of the trade in your backpack as possible. Like artists who choose which paintbrush to use to paint their masterpieces, writers need to be familiar with many different types of essays and patterns of organization, so that they may choose from their set of tools in order to find the one that will aid them in creating their masterpieces. ReferencesBrady, J. (1971). I want a wife. New York Magazine. p. 59-60. Road trip. (2014). In Merriam-Webster's online dictionary. Retrieved from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/roadtrip. Franklin, B. (1786). The art of procuring pleasant dreams. Retrieved http://grammar.about.com/od/classicessays/a/pleasantdreams.htm Herbert, A. (1920). About bathrooms. Retrieved from http://grammar.about.com/od/classicessays/a/About-Bathrooms-By-A-p-Herbert.htm Rhys, G. (1920). A brother of St. Francis. Retrieved from http://grammar.about.com/od/classicessays/a/BrotherOfStFrancis.htm |