Show Navigation Menu

Section Two : Becoming a Researcher/Scholar

Introduction | Definitions of Critical Thinking | Critical Thinking in Practice |

Metacognition | Comparative Analysis and Comparative Research | Conclusion | References

Chapter 6: Critical Thinking: The Means to Inquire

Hide Navigation Menu

Home Page

Section 2 Becoming a Researcher/Scholar / Chapter 6 Critical Thinking: The Means to Inquire

5. Comparative Analysis and Comparative Research

If comparison refers to an examination of similarity or dissimilarity between two objects, analysis refers to the examination of the component parts of subject or object for purposes of discussion, and research refers to the examination of the constituent parts of a subject or object as a basis for ascertaining fact or drawing conclusions, then comparative analysis can be described as a general examination of wider bodies of information. Also, comparative research can be described as a narrow examination of very specific bodies of information or an acute examination of data sets. Comparative analysis is general and comparative research is focused.

In the course of conducting comparative analysis, perhaps through the use of a comparison matrix, scholars can move beyond cursory identification and presentation of component parts of research articles. Such analysis moves from what might be called the eyeball test, in which the viewer relies solely upon what is observed on a surface level, to a deeper, more nuanced analysis of new information in a specific context, supported by a review of the literature. Scholars can begin to draw upon resources and ideas from other perspectives to think differently about the information being processed. What information do scholars bring to new observations? That is to say, how have a given set of understandings been formed or informed such that highly focused research is created within in a distinct field of interest?

Synthesis of Disparate Information

What does synthesis mean in terms of critical thinking? Synthesis, in its most basic form, means taking two or more different ideas and making them relevant to one another. This means doctoral learners likely will be drawing on more than two or three different perspectives to establish their focal point. Further, this likely will mean doctoral learners will have to support their main points from perspectives that may exist in different contexts.

Take, for instance, an observation about sick bee colonies drawn from reading a newspaper of magazine. What do sick honey bees have to do with macroeconomics, ecosystems, and agriculture? The lines may not be too terribly difficult to draw if it is understood that bees pollinate plants, providing larger crop yields, and a stronger agriculture base. A line of inquiry might start out by attempting to understand honey-bee populations (entomology) and global agriculture markets (economics). Further, if a determination can be made as to which parts of the country rely on or provide high agriculture exports and the percentage of national exports comprised of agriculture products, a more well-rounded and focused perspective of the importance of maintaining healthy bee colonies is established. So, coming full circle to an analysis of the effects of sick honey bees on global agriculture markets, sick bees, potentially, means less agriculture, which means there is less to sell to the nation and the world. Suddenly, healthy bees become a more visible issue to address.

Synthesizing Disparate Information

What is disparate information? In a general sense, it is a disparity between two objects that upon first glance appear diametrically opposed or lacking in similarity. For example, what do the Apatosaurus and toothbrushes have in common? At first glance, an examination of dinosaurs and toothbrushes appears arcane. Consider the following question: What does a 20-ton dinosaur have to do with a toothbrush that fits in the palm of a hand? To engage this question, consider a few characteristics of each. The Apatosaurus, also, mistakenly, called Brontosaurus, was an herbivore thought to have stood on its hind legs to use its height and long neck to reach high into the canopy and forage among the treetops. The toothbrush has become both a useful implement to maintain oral health, According to the Library of Congress, an early toothbrush appeared as early as 4000 BC (Library of Congress, 2010). This early brush was nothing more than a twig with frayed ends, called a chew stick. Not until 1938, when the DuPont company produced the first nylon bristle toothbrush, has the tool delivered the utility and shape known today. Nylon bristles helped the brush last longer, and the smaller head and straight, flexible neck and handle meant the user could get to all the hard to reach places in the back of their mouth (Library of Congress, 2010).

With that information, consider the question again. What does the Apatosaurus and toothbrushes have in common? Both have longnecks and small heads, useful for getting at hard-to-reach places. This example may be oversimplified; however, the point remains the same: Conclusions are drawn based on analysis of two seemingly disparate subjects, broken down into the component parts of each.

Sidebar 1: Focused Research, Research from the Field

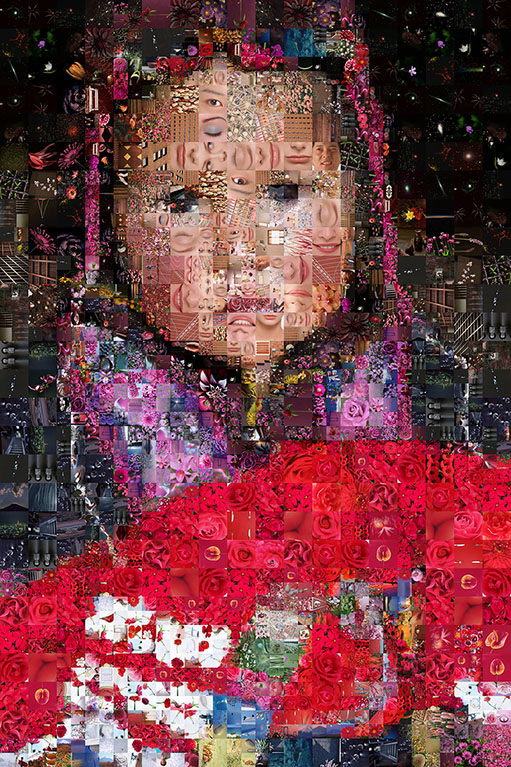

Sidebar 2: Disparate Subjects, Critical Thinker: Malcolm Gladwell